The Shape of AI: Jaggedness, Bottlenecks and Salients

And why Nano Banana Pro is such a big deal

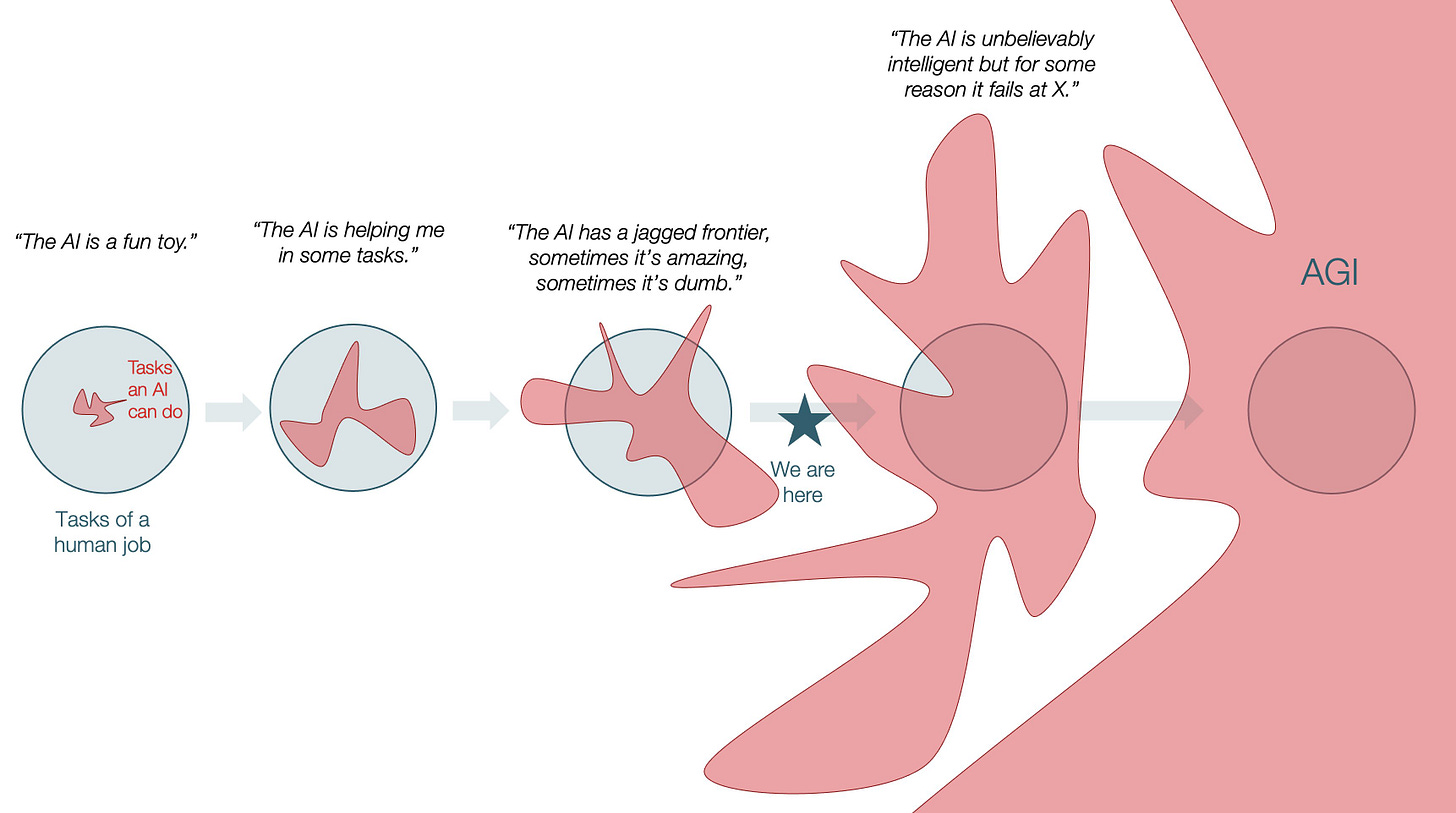

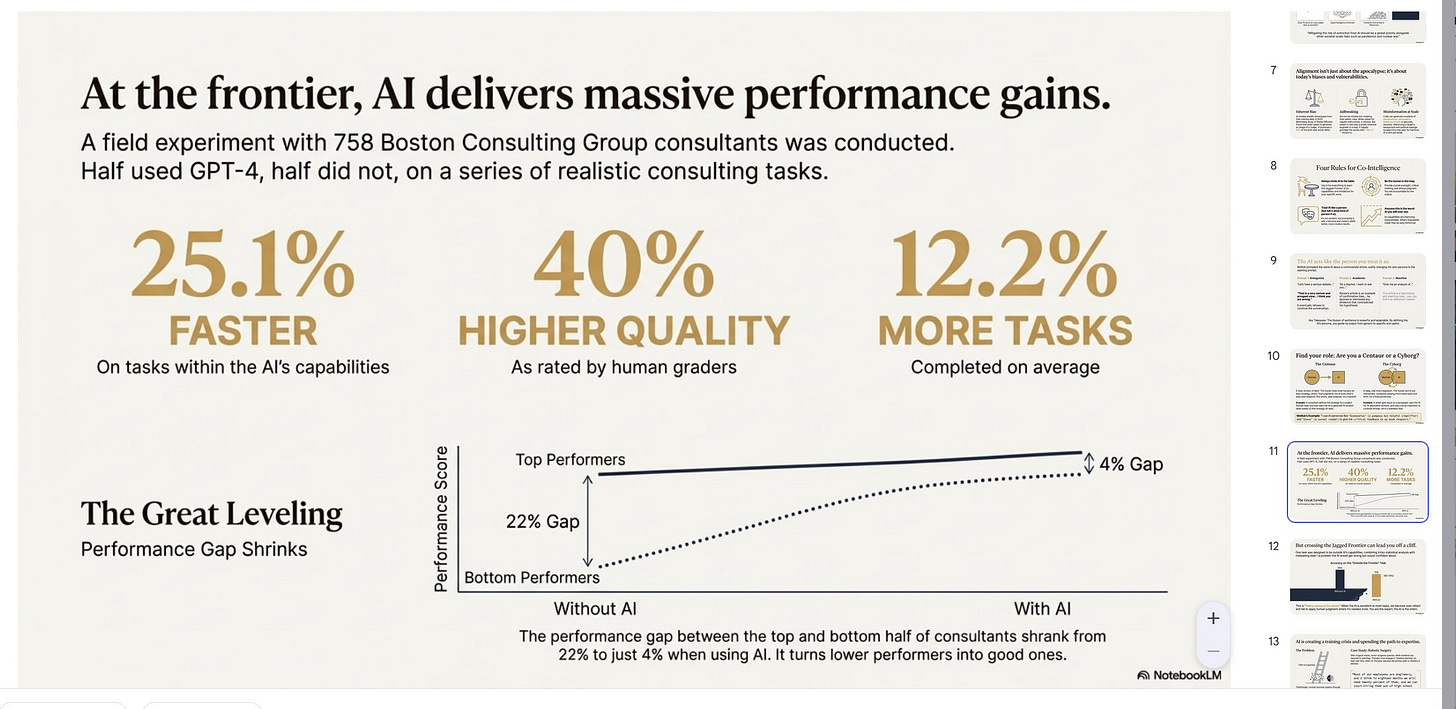

Back in the ancient AI days of 2023, my co-authors and I invented a term to describe the weird ability of AI to do some work incredibly well and other work incredibly badly in ways that didn’t map very well to our human intuition of the difficulty of the task. We called this the “Jagged Frontier” of AI ability, and it remains a key feature of AI and an endless source of confusion. How can an AI be superhuman at differential medical diagnosis or good at very hard math (yes, they are really good at math now, famously outside the frontier until recently) and yet still be bad at relatively simple visual puzzles or running a vending machine? The exact abilities of AI are often a mystery, so it is no wonder AI is harder to use than it seems.

I think jaggedness is going to remain a big part of AIs going forward, but there is less certainty over what it means. Tomas Pueyo posted this viral image on X that outlined his vision. In his view, the growing frontier will outpace jaggedness. Sure, the AI is bad at some things and may still be relatively bad even as it improves, but the collective human ability frontier is mostly fixed, and AI ability is growing rapidly. What does it matter if AI is relatively bad at running a vending machine, if the AI still becomes better than any human?

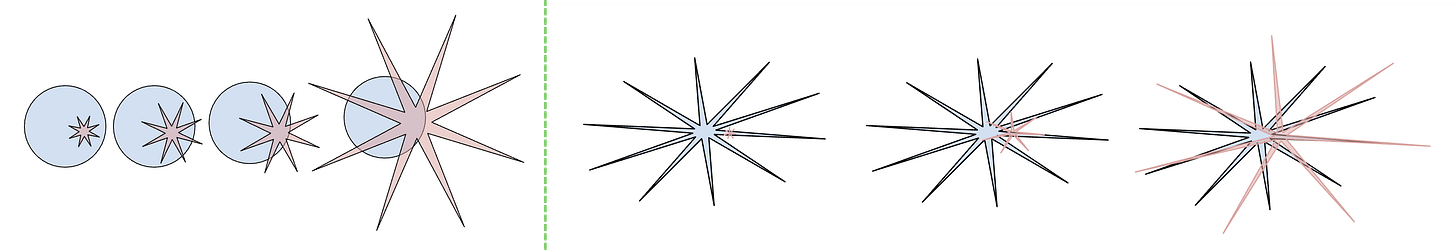

While the future is always uncertain, I think this conception misses out on a few critical aspects about the nature of work and technology. First, the frontier is very jagged indeed, and it might be that, because of this jaggedness, we get supersmart AIs which never quite fully overlap with human tasks. For example, a major source of jaggedness is that LLMs do not remember new tasks and learn from them in a permanent way. A lot of AI companies are pursuing solutions to this issue, but it may be that this problem is harder to solve than researchers expect. Without memory, AIs will struggle to do many tasks humans can do, even while being superhuman in other areas. Colin Fraser drew two examples of what this sort of AI-human overlap might look like. You can see how AI is indeed superhuman in some areas, but in others it is either far below human level or not overlapping at all. If this is true, then AI will create new opportunities working in complement with human beings, since we both bring different abilities to the table.

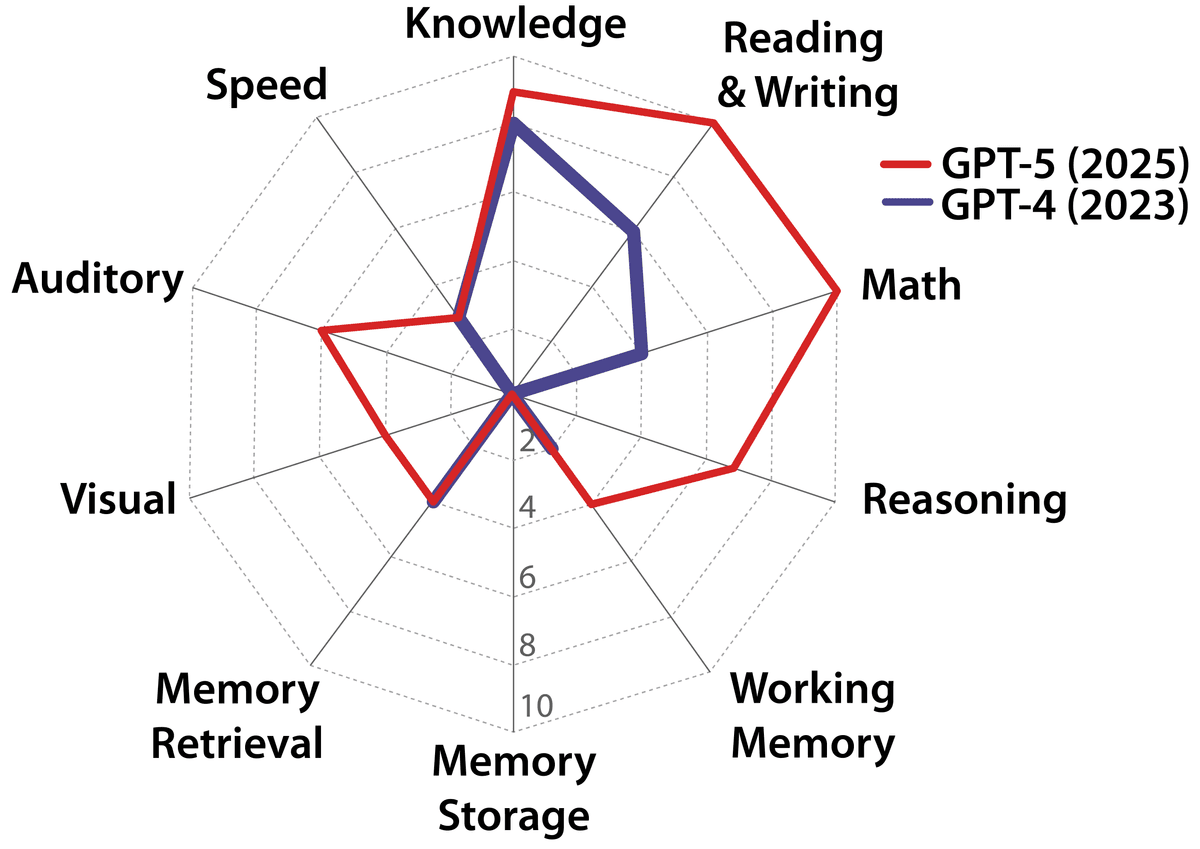

These are conceptual drawings, but a group of scientists recently tried to map the shape of AI ability and found that it was growing unevenly, just as the jagged frontier would predict. Reading, math, general knowledge, reasoning — all were things that AI was improving on rapidly. But memory, as we discussed, is a weak spot with very little improvement. Better prompting or better models (and GPT-5.2 is much better than GPT-5) might change the shape of the frontier, but jaggedness remains.

Bottlenecks

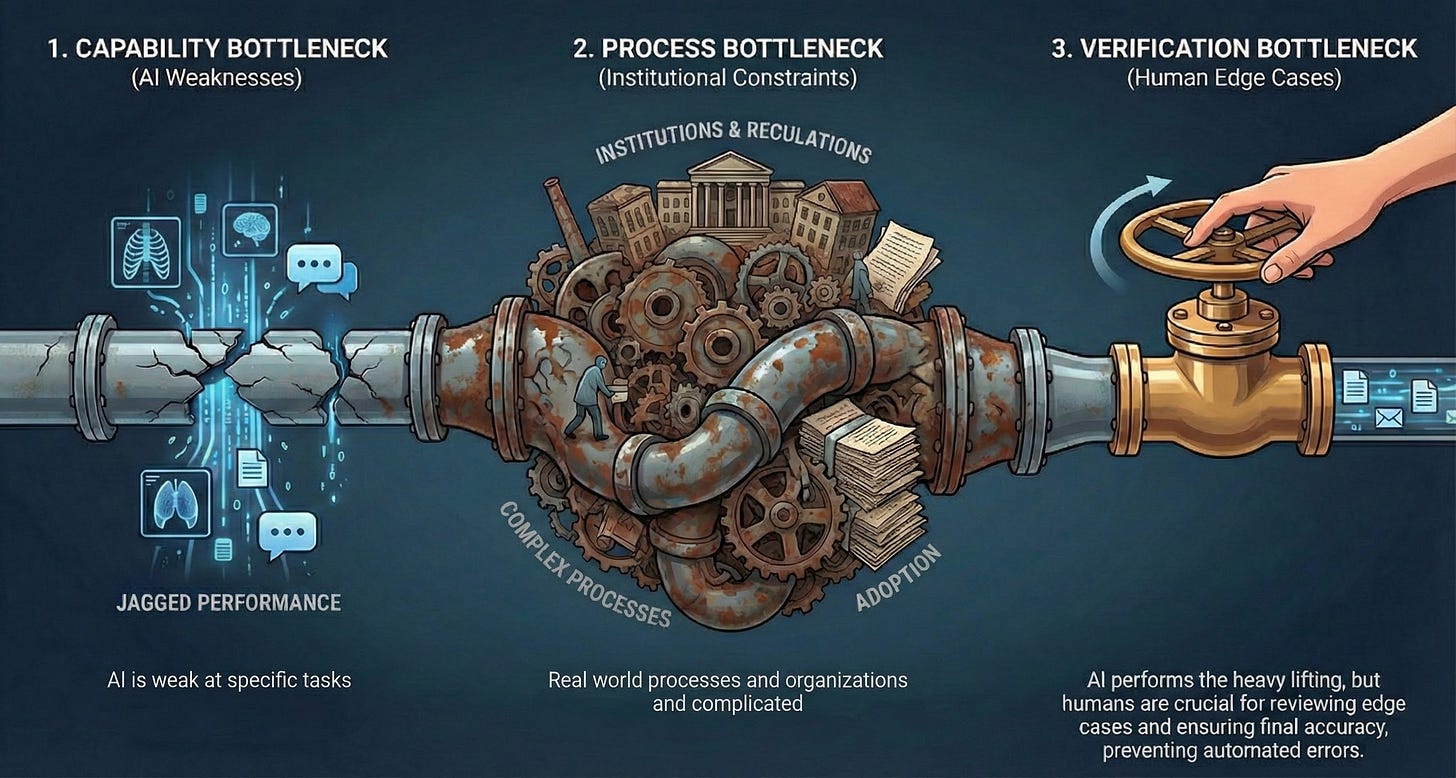

And even small amounts of jaggedness can create issues that make super-smart AIs unable to automate a task. A system is only as functional as its worst components. We call these problems bottlenecks. Some bottlenecks are because the AI is stubbornly subhuman at some tasks. LLM vision systems aren’t good enough at reading medical imaging so they can’t yet replace doctors; LLMs are too helpful when they should push back so they can’t yet replace therapists; hallucinations persist even if they have become rarer which means they can’t yet do tasks where 100% accuracy is required; and so on. If the frontier continues to expand, some of these problems may disappear, but weaknesses are not the only form of bottleneck.

Some bottlenecks are because of processes that have nothing to do with ability. Even if AI can now identify promising drug candidates dramatically faster than traditional methods, clinical trials still need actual human patients who take actual time to recruit, dose, and monitor. The FDA still requires human review of applications. Even if AI increases the rate of good drug ideas by ten times or more, the constraint becomes the rate of approval, not the rate of discovery. The bottleneck migrates from intelligence to institutions, and institutions move at institution speed.

And even where the AI is almost completely superhuman, humans may be needed for edge cases. As an example, take a study that used AI to reproduce Cochrane reviews, the famous deeply researched meta-studies that synthesize many medical studies to figure out the scientific consensus on a topic. A team of researchers found that GPT-4.1, when properly prompted and supported, “reproduced and updated an entire issue of Cochrane reviews (n=12) in two days, representing approximately 12 work-years of traditional systematic review work.” The AI screened over 146,000 citations, read full papers, extracted data, and ran statistical analyses. It actually outperformed human reviewers on accuracy. Oddly, much of the hard intellectual work — finding relevant studies, pulling the right numbers, synthesizing results — is solidly inside the frontier. But the AI can't access supplementary files and it can't email authors to request unpublished data, things human reviewers do routinely. This makes up less than 1% of errors in the review, but those errors mean you can't fully automate the process. Twelve work-years become two days, but only if a human with expertise in how science is actually done handles the edge cases.

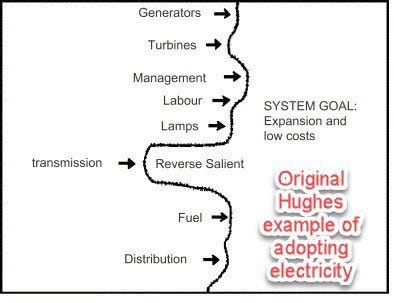

This is the pattern: jaggedness creates bottlenecks, and bottlenecks mean that even very smart AI cannot easily substitute for humans. At least not yet. This is likely good in some ways (preventing rapid job loss) but frustrating in others (making it hard to speed up scientific research as much as we might hope). Bottlenecks also concentrate the work of AI companies into making the AI better at things that are holding it back, the way math ability rapidly improved once it became an obvious barrier. The historian Thomas Hughes had a term for this. Studying how electrical systems developed, he noticed that progress often stalled on a single technical or social problem. He called these “reverse salients” - the one technical or social problem holding back the system from leaping ahead.

Reverse Salients

Bottlenecks can create the impression that AI will never be able to do something, when, in reality, progress is held back by a single jagged weakness. When that weakness becomes a reverse salient, and AI labs suddenly fix the problem, the entire system can jump forward.

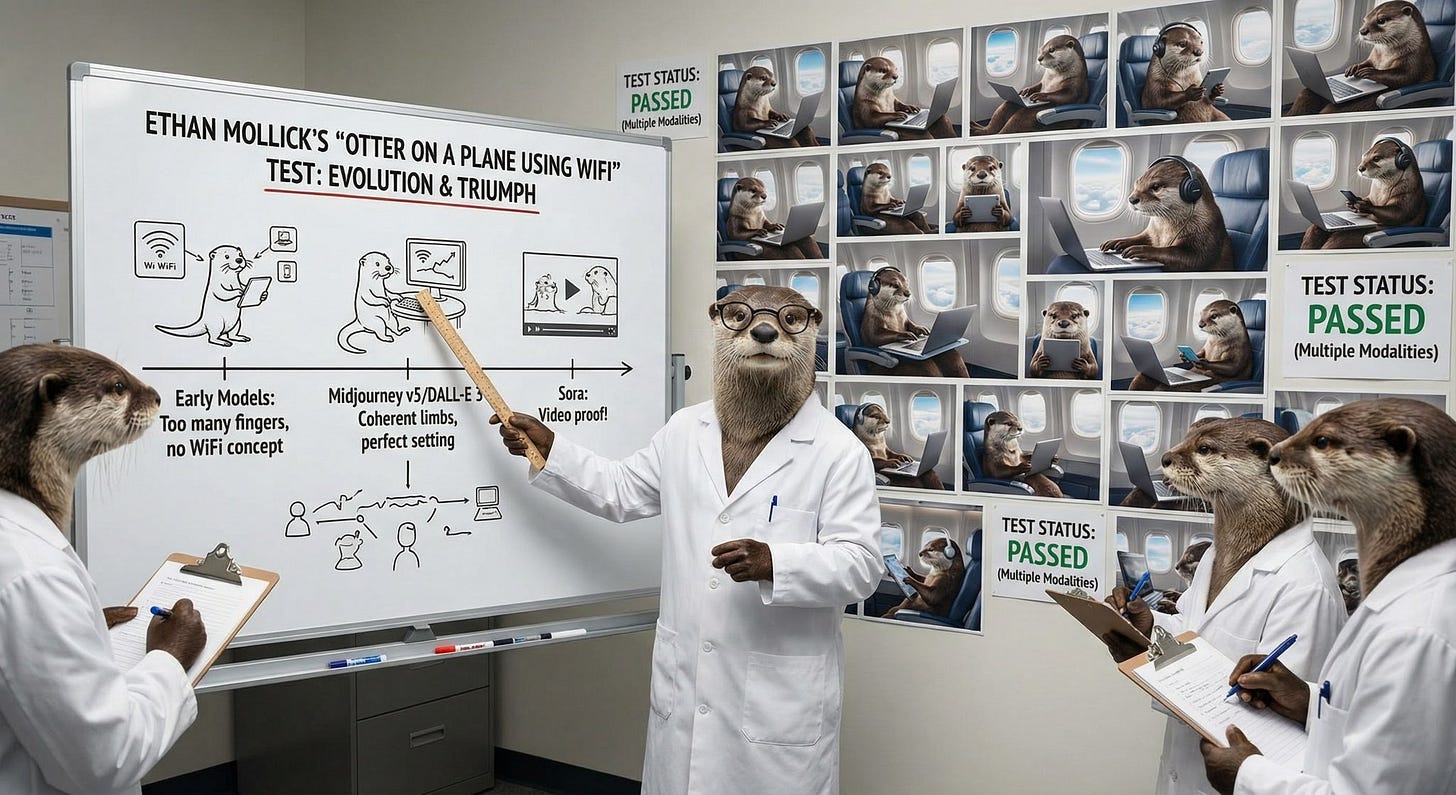

The most powerful example of this from the last month is Google’s new image generation AI, Nano Banana Pro (yes, AI companies are still bad at naming things). It combines two advances: a very good image creation model and a very smart AI that can help direct the model, looking up information as needed. For example, if I prompt Nano Banana Pro for the ultimate version of my otter test: “Scientists who are otters are using a white board to explain ethan mollicks otter on a plane using WiFi test of AI (you must search for this) and demonstrating it has been passed with a wall full of photos of otters on planes using laptops.” I get this:

Coherent words, different angles, shadows, no major misspellings. Pretty amazing stuff. Remember, the prompt “otter on a plane using wifi” got this image in 2021:

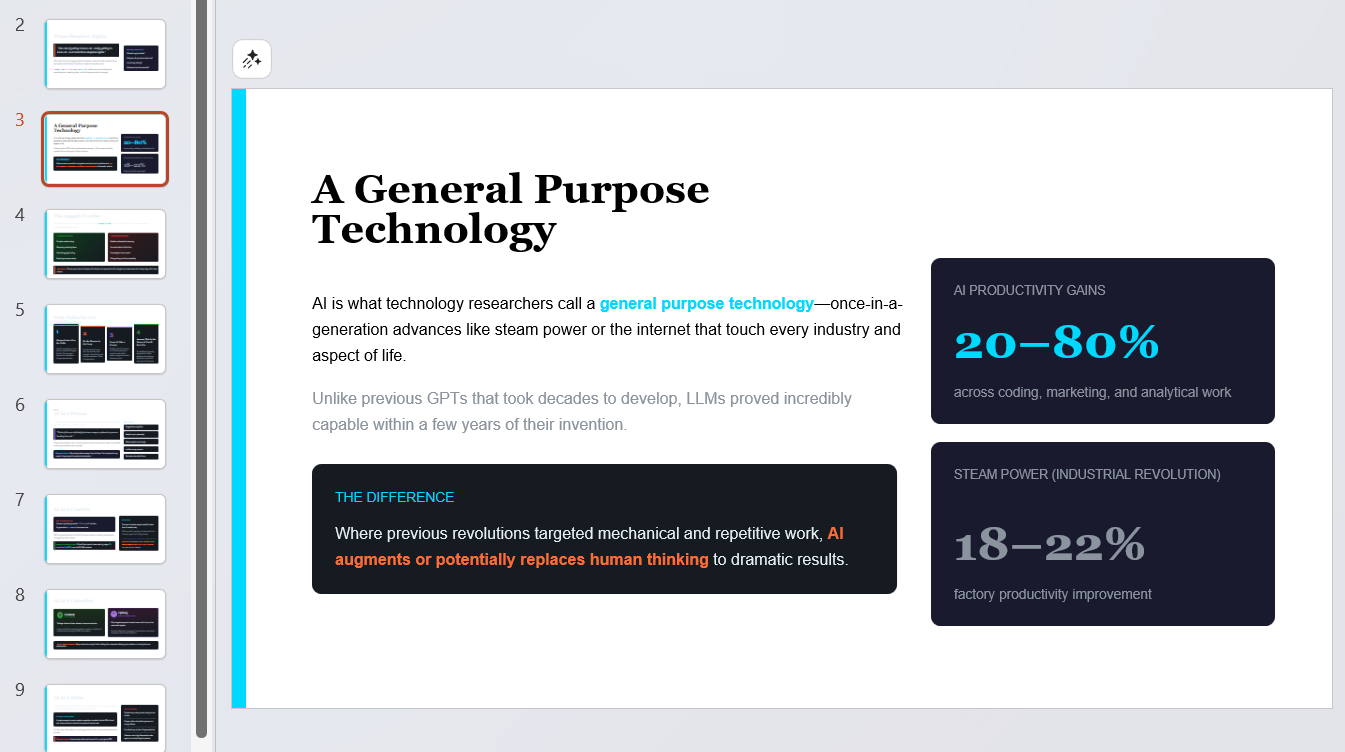

But it turns out that really good image generation was the bottleneck for a lot of new capabilities. For example, take PowerPoint decks. Every major AI company has been trying to get their AI to make PowerPoint, and they have done this by having the AIs write computer code (which they are very good at) to create a PowerPoint from scratch. This is a hard process, but both Claude and ChatGPT have improved a lot, even if their slides are a little dull. For example, I took my book, Co-Intelligence, and threw it into Claude and asked for a slide deck summary. The model is very smart, but the PowerPoint deck is limited by the fact that it has to be written in code.

Now here is the same thing in Google’s NotebookLM application, using its smart Gemini AI model combined with Nano Banana Pro. It isn’t using code, it is creating each slide as a single image. When image quality was low, this would have been impossible. Suddenly, it isn’t.

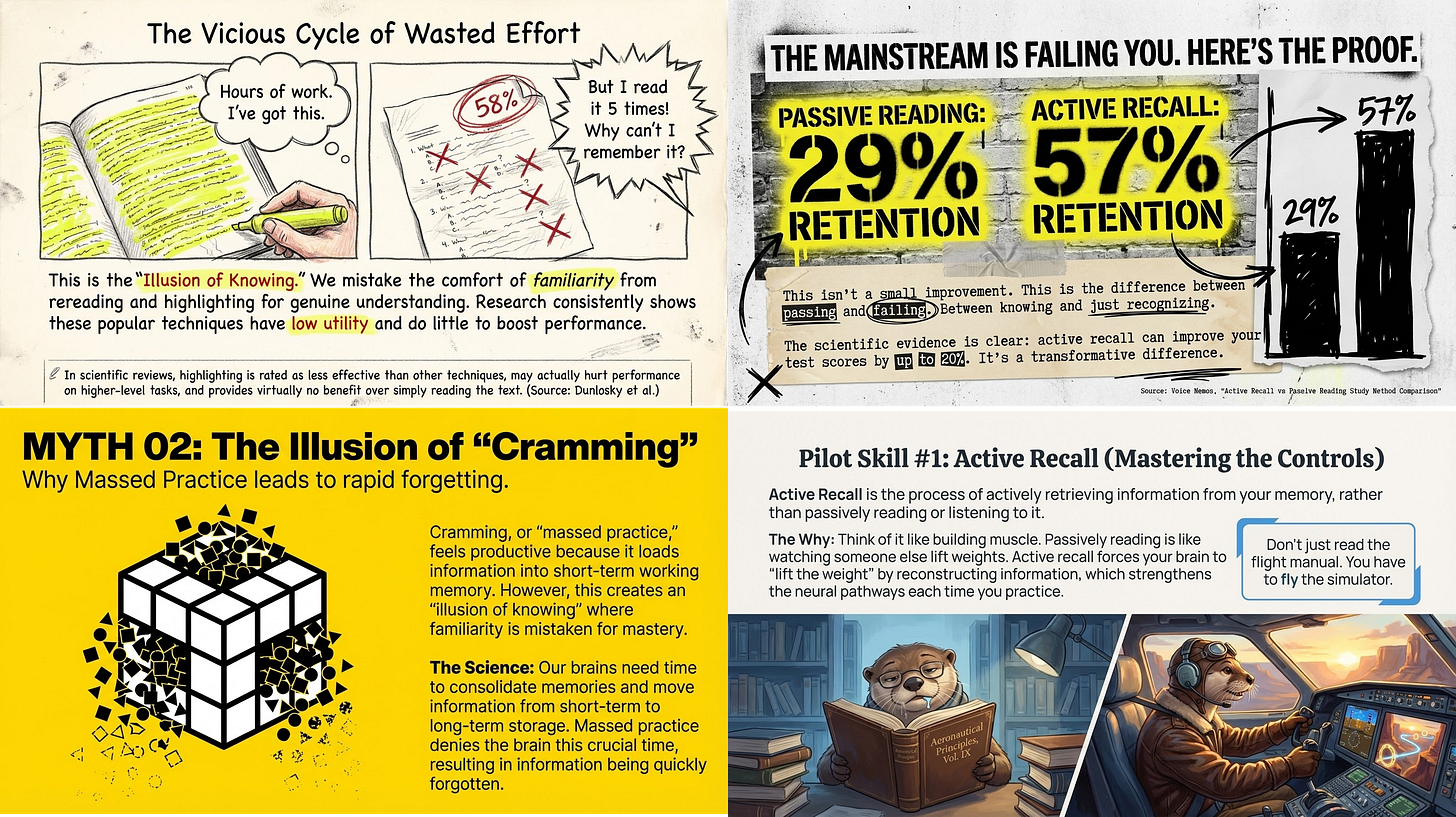

And since images are very flexible, I can play with style and approach. I had NotebookLM do a deep research report on science-backed methods of learning and then turn that into dense slide decks meant for reading in a variety of styles: one that looked hand-drawn, one that was inspired by 1980s punk, one that was “very dramatic and high contrast slides with a bright yellow background,” and, of course, one with an otter-on-a-plane theme.

In many ways, the hard stuff is inside the frontier for both Claude and Gemini, they can just take source materials, a topic, and an idea and summarize it in a slide. Hallucinations are very rare, and the sources are correct. It can create otter analogies or come up with a punk-themed description. This is the intellectually demanding part, and AIs have been capable of it for over a year. But making slides or other visual presentations was a bottleneck to making walls of text useful. The problem isn’t completely solved: images are not perfect, and you can’t edit them (apparently this will be fixed soon), but you can see where things are going.

Many lurches

Even if AI becomes superhuman at analysis and PowerPoint, I don’t think that means AI necessarily replaces the jobs of consultants and designers. Those jobs consist of many different tasks along the jagged frontier that AI is bad at and which humans excel: can you collect information and get buy-in from the many parties involved? Can you understand the unwritten rules that determine what people actually need? Can you come up with something unique to address a deep issue, that stands out from AI material? The jagged frontier offers many opportunities for human work.

Yet, we should expect to see lurches forward, where focusing on reverse salients leads to sudden removals of bottlenecks. Areas of work that used to be only human become something that AI can do. If you want to understand where AI is headed, don’t watch the benchmarks. Watch the bottlenecks. When one breaks, everything behind it comes flooding through. Image generation was holding back presentations, documents, visual communication of all kinds. Now it isn’t. What’s the next bottleneck? Memory? Real-time learning? The ability to take actions in the physical world?

Somewhere, right now, an AI lab is treating each of these bottlenecks as a reverse salient. We won’t get much warning when they break through. But a jagged frontier cuts both ways. So far, every lurch forward leaves yet more edges in which humans are needed. There will be many lurches ahead. There will also be many opportunities. Pay attention to both.

As you point out, the shape of the jagged frontier results from decisions made at the labs (eg: attack a reverse salient). So it might be nice if they aimed at co-intelligence rather than uber-intelligence and delivered a shape that complements our human boundary, rather than attempts to circumscribe it.

Ethan, Interesting! Here are my 2 takeaways: The "jaggedness" means you can't fully replace human workers, but you can dramatically accelerate certain parts of their work. The "jagged frontier" also means your job isn't going away, it's transforming into managing AI across those edges where humans remain essential.

I'm a non-tech co-founder of an AI company that focuses on the human side and enjoy reading your articles. It keeps me in the know, but I had to create an AI assistant that turns high tech articles into human speak for muggles like me - https://pria.praxislxp.com/views/history/6946e9da0e1af8fb14030dca