Mass Intelligence

From GPT-5 to nano banana: everyone is getting access to powerful AI

More than a billion people use AI chatbots regularly. ChatGPT has over 700 million weekly users. Gemini and other leading AIs add hundreds of millions more. In my posts, I often focus on the advances that AI is making (for example, in the past few weeks, both OpenAI and Google AIs chatbots got gold medals in the International Math Olympiad), but that obscures a broader shift that's been building: we're entering an era of Mass Intelligence, where powerful AI is becoming as accessible as a Google search.

Until recently, free users of these systems (the overwhelming majority) had access only to older, smaller AI models that frequently made mistakes and had limited use for complex work. The best models, like Reasoners that can solve very hard problems and hallucinate much less often, required paying somewhere between $20 and $200 a month. And even then, you needed to know which model to pick and how to prompt it properly. But the economics and interfaces are changing rapidly, with fairly large consequences for how all of us work, learn, and think.

Powerful AI is Getting Cheaper and Easier to Access

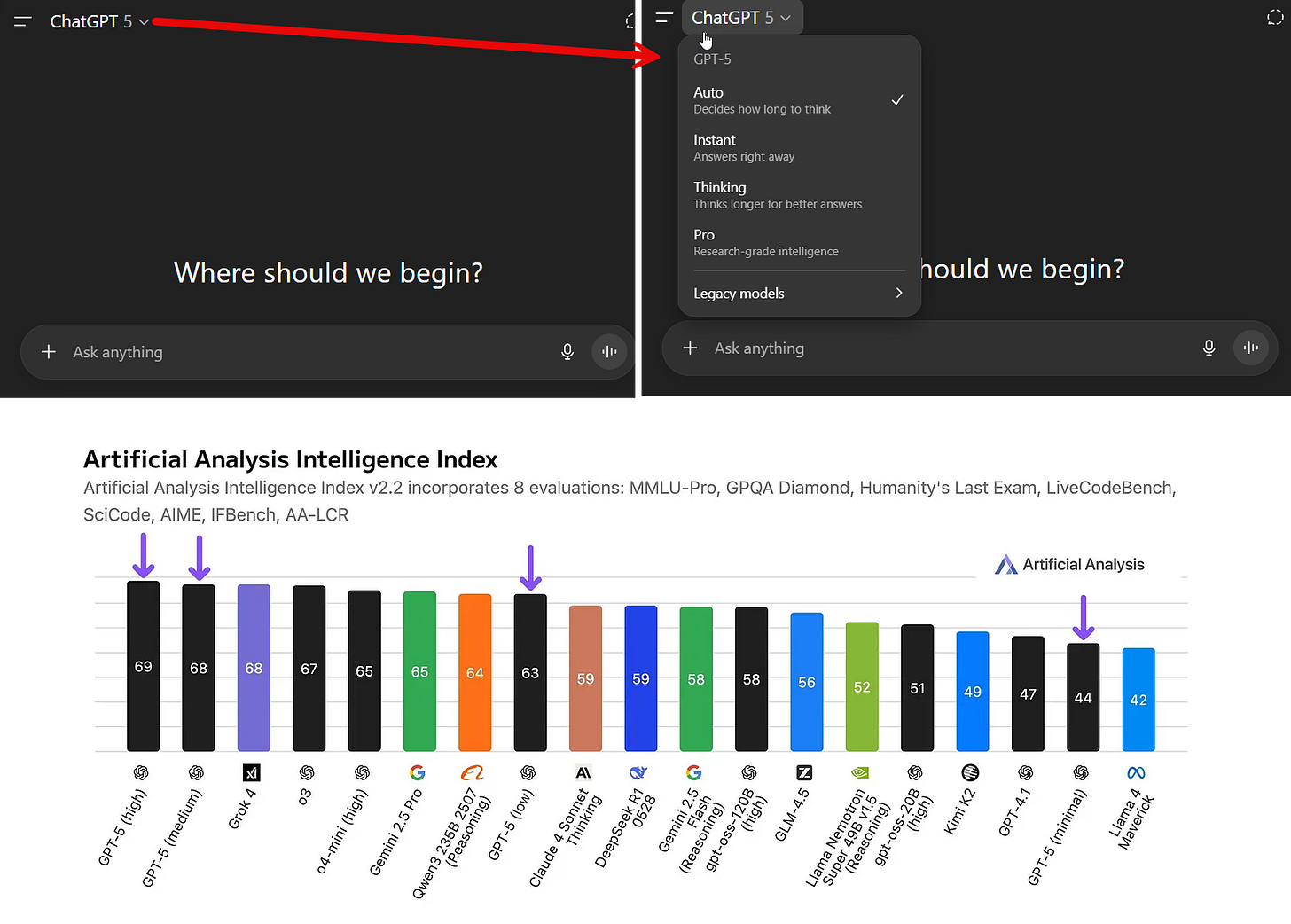

There have been two barriers to accessing powerful AI for most users. The first was confusion. Few people knew to select an AI model. Even fewer knew that picking o3 from a menu in ChatGPT would get them access to an excellent Reasoner AI model, while picking 4o (which seems like a higher number) would give them something far less capable. According to OpenAI, less than 7% of paying customers selected o3 on a regular basis, meaning even power users were missing out on what Reasoners could do.

Another factor was cost. Because the best models are expensive, free users were often not given access to them, or else given very limited access. Google led the way in giving some free access to its best models, but OpenAI stated that almost none of its free customers had regular access to reasoning models prior to the launch of GPT-5.

GPT-5 was supposed to solve both of these problems, which is partially why its debut was so messy and confusing. GPT-5 is actually two things. It was the overall name for a family of quite different models, from the weaker GPT-5 Nano to the powerful GPT-5 Pro. It was also the name given to the tool that picked which model to use and how much computing power the AI should use to solve your problem. When you are writing to “GPT-5” you are actually talking to a router that is supposed to automatically decide whether your problem can be solved by a smaller, faster model or needs to go to a more powerful Reasoner.

You could see how this was supposed to expand access to powerful AI to more users: if you just wanted to chat, GPT-5 was supposed to use its weaker specialized chat models; if you were trying to solve a math problem, GPT-5 was supposed to send you to its slower, more expensive GPT-5 Thinking model. This would save money and give more people access to the best AIs. But the rollout had issues. This practice wasn’t well explained and the router did not work well at first. The result is that one person using GPT-5 got a very smart answer while another got a bad one. Despite these issues, OpenAI reported early success. Within a few days of launch, the percentage of paying customers who had used a Reasoner went from 7% to 24% and the number of free customers using the most powerful models went from almost zero to 7%.

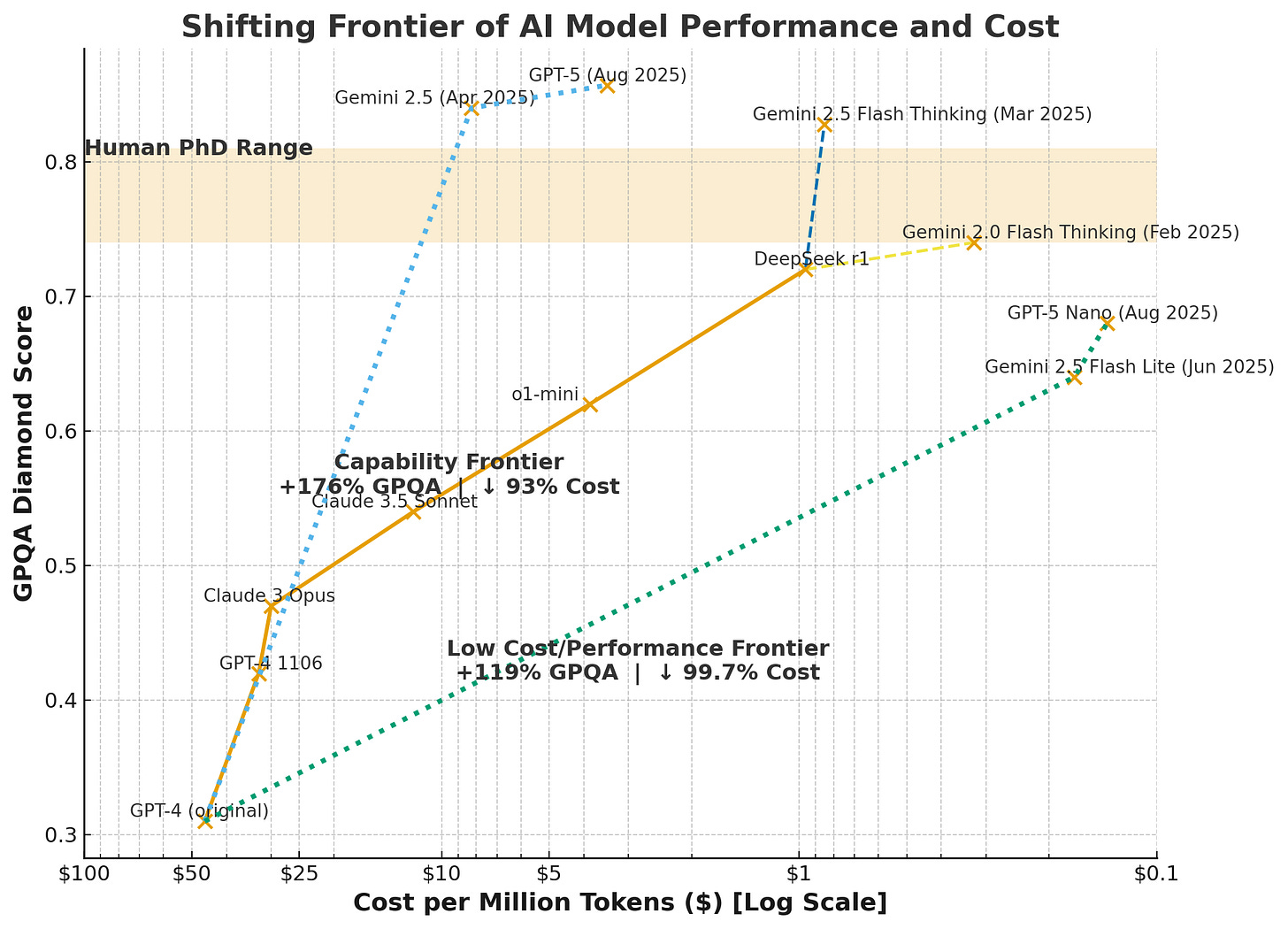

Part of this change is driven by the fact that smarter models are getting dramatically more efficient to run. This graph shows how fast this trend has played out, mapping the capability of AI on the y-axis and the logarithmically decreasing costs on the x-axis. When GPT-4 came out it was around $50 to work with a million tokens (a token is roughly a word), now it costs around 14 cents per million tokens to use GPT-5 nano, a much more capable model than the original GPT-4.

This efficiency gain isn't just financial, it's also environmental. Google has reported that energy efficiency per prompt has improved by 33x in the last year alone. The marginal energy used by a standard prompt from a modern LLM in 2025 is relatively established at this point, from both independent tests and official announcements. It is roughly 0.0003 kWh, the same energy use as 8-10 seconds of streaming Netflix or the equivalent of a Google search in 2008 (interestingly, image creation seems to use a similar amount of energy as a text prompt)1. How much water these models use per prompt is less clear but ranges from a few drops to a fifth of a shot glass (.25mL to 5mL+), depending on the definitions of water use (here is the low water argument and the high water argument).

These improvements mean that even as AI gets more powerful, it's also becoming viable to give to more people. The marginal cost of serving each additional user has collapsed, which means more business models, like ad support, become possible. Free users can now run prompts that would have cost dollars just two years ago. This is how a billion people suddenly get access to powerful AIs: not through some grand democratization initiative, but because the economics finally make it possible.

Powerful AI is Getting Easy to Use

Getting access to a powerful AI is not enough, people need to actually use it to get things done. Using AI well used to be a pretty challenging process which involved crafting a prompt using techniques like chain-of-thought along with learning tips and tricks to get the most out of your AI. In a recent series of experiments, however, we have discovered that these techniques don’t really help anymore. Powerful AI models are just getting better at doing what you ask them to or even figuring out what you want and going beyond what you ask (and no, threatening them or being nice to them does not seem to help on average).

And it isn’t just text models that are becoming cheaper and easier to use. Google released a new image model with the code name “nano banana” and the much more boring official name Gemini 2.5 Flash Image Generator. In addition to being excellent (though better at editing images than creating new ones), it is also cheap enough that free users can access it. And, unlike previous generations of AI image generators, it follows instructions in plain language very well.

As an example of both its power and ease of use, I uploaded an iconic (and copyright free) image of the Apollo 11 astronauts and a random picture of a sparkly tuxedo and gave it the simplest prompts: “dress Neil Armstrong on the left in this tuxedo”

Here is what it gave me a few seconds later:

There are issues that someone with an expert eye would spot, but it is still impressive to see the realistic folds of the tuxedo and how it is blended into the scene (the NASA pin on the lapel was a nice touch). There is still a lot of randomness in the process that makes AI image editing unsuitable for many professional applications, but for most people, this represents a huge leap in not just what they can do, but how easy it is to do it.

And we can go further: “now show a photograph where neil armstrong and buzz aldrin, in the same outfits, are sitting in their seats in a modern airplane, neil looks relaxed and is leaning back, playing a trumpet, buzz seems nervous and is holding a hamburger, in the middle seat is a realistic otter sitting in a seat and using a laptop.”

This is many things: A pretty impressive output from the AI (look at the expressions, and how it preserved Buzz’s ring and Neil’s lapel pin). A distortion of a famous moment in history made possible by AI. And a potential warning about how weird things are going to get when these sorts of technologies are used widely.

The Weirdness of Mass Intelligence

When powerful AI is in the hands of a billion people, a lot of things are going to happen at once. A lot of things are already happening at once.

Some people have intense relationships with AI models while other people are being saved from loneliness. AI models may be causing mental breakdowns and dangerous behavior for some while being used to diagnose the diseases of others. It is being used to write obituaries and create scriptures and cheat on homework and launch new ventures and thousands of other unexpected uses. These uses, and both the problems and benefits, are likely to only multiply as AI systems get more powerful.

And while Google's AI image generator has guardrails to limit misuse, as well as invisible watermarks to identify AI images, I expect much less restrictive AI image generators will likely get close to nano banana in quality in the coming months.

The AI companies (whether you believe their commitments to safety or not) seem to be as unable to absorb all of this as the rest of us are. When a billion people have access to advanced AI, we've entered what we might call the era of Mass Intelligence. Every institution we have — schools, hospitals, courts, companies, governments — was built for a world where intelligence was scarce and expensive. Now every profession, every institution, every community has to figure out how to thrive with Mass Intelligence. How do we harness a billion people using AI while managing the chaos that comes with it? How do we rebuild trust when anyone can fabricate anything? How do we preserve what's valuable about human expertise while democratizing access to knowledge?

So here we are. Powerful AI is cheap enough to give away, easy enough that you don't need a manual, and capable enough to outperform humans at a range of intellectual tasks. A flood of opportunities and problems are about to show up in classrooms, courtrooms, and boardrooms around the world. The Mass Intelligence era is what happens when you give a billion people access to an unprecedented set of tools and see what they do with it. We are about to find out what that is like.

This is the energy required to answer a standard prompt. It does not take into account the energy needed to train AI models, which is a one-time process that is very energy intensive. We do not know how much energy is used to create a modern model, but it was estimated that training GPT-4 took a little above 500,000 kWh, about 18 hours of a Boeing 737 in flight.

I want to be optimistic for when we have ASI (Artificial Super Intelligence). My reasoning is simple. Every day the headline news proves conclusively that leaders of nations and their governments are not especially intelligent. If they were, they would realise that climate change, warfare, famine, and other factors that could lead to societal and environmental collapse are all the results of poor decision-making or no decision-making - particularly when so many solutions to these problems exist but are ignored. No individual leader, government, corporate or organisational body is capable of taking decisions free from, variously, political bias, personal prejudice, revenge, religious belief, greed, feelings of animosity to others etc, etc. I can, however, imagine an Artificial Super Intelligence, that can do far better than this. Of course, the creation of this utopia depends entirely on the motives of the people behind it. I wouldn't trust Musk or Zuckerberg as far as I could throw them. Of course, if it really is super intelligent, it will be clever enough to ignore any nefarious instructions it's been given. By then, I also hope, ChatGPT will have stopped saying, "That's a really good question".

It wasn't that long ago that we had NO way to verify information, besides trust or experience. We've lived in a small period of time where verification of events or information was even possible.

Ultimately, we have to resort back to the old technique of asking people we know are reliable. Sadly, we also know exactly how bad the human memory is with creative reconstruction, so the window of having objectively verifiable events may be coming to a close.

The progress also makes me wonder about the inherent issues with our languages for conveying meaning. The more I use LLMs, the more it feels like conveying meaning was always just one big game of Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.

Different languages and dialects can be used to convey a variety of intents. "Who be eat'in cookies?" conveys a very different idea than "Who is eating cookies?". It's much closer to "Who is known for eating cookies?". The simple grammar feature, and understanding of it - can drastically change the meaning of the phrase.

We are finally going to have to accept the humanities people into the tech playhouse.