Innovation through prompting

Democratizing educational technology... and more

If you have been reading my Substack (or my new book, which made the New York Times bestseller list!), you know that one of the things I find most exciting about AI is its potential for expanding the number of people able to produce and share useful innovations. I am particularly interested in how prompts can work as a sort of “program in prose” that can be tailored to many different industries and fields, and which can be created by non-technical experts.

This works because LLMs are extremely powerful tools that are remarkably easy to use, and whose capabilities can be wielded by anyone who can write or speak. And, while there are reasons to build more complex technological solutions, simple prompts given to a GPT-4 class chatbot can allow non-programmers to accomplish impressive things. Plus, while barriers to access remain, it helps that you can use LLMs on a mobile phone, and that powerful models are rapidly getting cheaper to use (the big news last week was the release of Llama 3, the open source AI from Meta that is already better than ChatGPT-3.5, and which will dramatically lower the prices for advanced AI access). This makes LLMs a good base on which to innovate.

But what does democratizing innovation with AI prompts actually look like? We have a new paper out today that tries to show one potential path. It specifically focuses on education, but I think the lessons are broadly applicable.

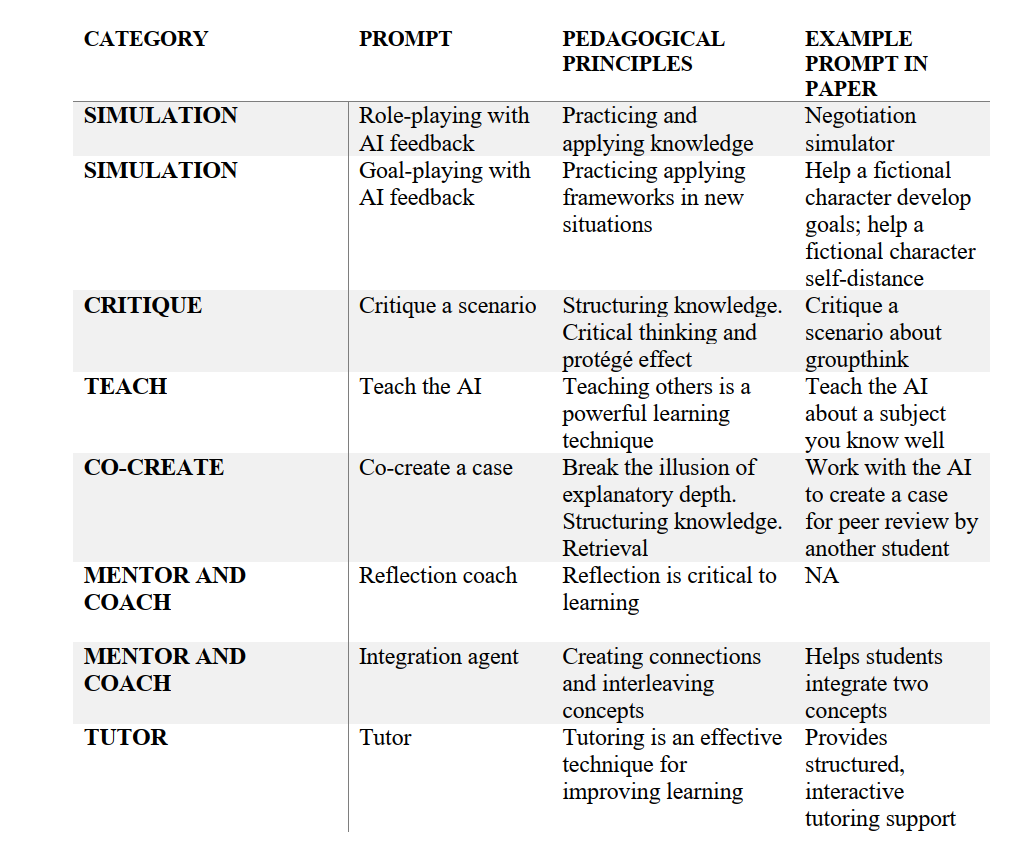

We took a context we know well, interactive teaching tools and pedagogy, and created research-based exercises that would have been difficult or impossible to do before the advent of generative AI. For example, the ability to generate a compelling educational simulation, with appropriate teaching support, using just a few paragraphs of text is an entirely new capability that AI has enabled. We have piloted a range of similar AI experiences in recent months, and they show considerable promise. While more experiments are needed on their effectiveness, these new tools expand the capabilities available to educators.

While I won’t discuss it here, in the paper we cover how to assign AI projects to students, as well as the ethical concerns, risks, and AI literacy issues that instructors need to consider. But, for this post, I want to concentrate on the exercises themselves, and specifically how they can help us understand the steps we can take in making AI prompts broadly useful. There is not just one way to use prompts in innovative ways, instead there multiple approaches that can work.

Level 1: Use a pre-made prompt

Just like instructors often share lesson plans, or members of organizations might share tips for success, people can also share prompts. This is a useful starting point for would-be-innovators; someone else has done the work of creating and testing a prompt for you. By using other people’s prompts, you can see what an AI system can (or can’t) do.

For example, here is a goal-play prompt you can try (GPT, Gemini Advanced link, and the paper has the full text of all the prompts). In a goal play, the AI sets up a scenario in which the student knows something the character in the simulation does not and guides the character using what they know, generally a framework they have to apply. In this case, students must apply a goal-setting framework to help a fictional character set goals. For fun, I decided to help out poor Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.

This alternate version of Hamlet might be a good scenario for students to practice goal-setting, but literature instructors are probably rolling their eyes. The scenario simplifies a complex Shakespeare play into a mere transactional situation (and doesn’t even use iambic pentameter). An exercise that is great in one setting can be terrible in another. That is why using someone else’s prompts is often a starting place for your own innovation, rather than an end point. Your environment and needs will often push you to create something to fill the voids that pre-made prompts cannot. And that’s a good thing! Prompting is not as hard as people think, and doing it well starts with experimentation.

Level 2: Customize or build a prompt

One way to experiment with advanced uses is to start with a pre-made prompt. In the paper, we provide annotated versions of all of the prompts we developed, so that you can see how you might need to customize one for yourself.

Ultimately, you may need to create a new prompt from scratch to accomplish your goals. As I have discussed, prompting is not an exact science, but you may be surprised about how effective prose instructions are. Still, any prompt requires testing and revision, so we developed a set of tests and remediation steps that might be useful to anyone trying to build their own prompts from scratch. Trial and error is going to be necessary to make something that works consistently.

Once you have created a new prompt, you should consider how to share it (our prompt library is here). In fact, if you want to encourage innovation, organizations need to consider, from the start, how they will create communities of practice around AI tools that also enable prompt sharing.

Level 3: Create tools that make tools

The next level of innovating through prompting is to help other people create their own innovations based on your knowledge. To do this, you need to develop tooling - prompts that can make prompts. This allows people to share not just a specific prompt, but their skill in prompt crafting. We call these kinds of prompts blueprints, and here is one that creates tutors (GPT, Gemini Advanced). You can take the text it creates and use it as a prompt to create a solid AI tutor tailored to a specific topic. This works much better than many generic tutor prompts because it is so focused and can be more easily tested by an expert instructor.

OpenAI’s GPT maker tool is an example of a blueprint, but we think much more tailored blueprints will be useful for many educators and organizations. They can help people build the prompts they need for specific situations.

Level 4: Just tell the AI what you want.

I suspect that many of the previous levels of prompt development will eventually become obsolete for most people. While there will still be value in creating prompts, increasingly AIs will just prompt themselves to solve your problem based on your goals.

Here is an example of me using Devin, an early AI agent powered by GPT-4. Rather than creating the perfect prompt, I can simply tell Devin “create and deploy a website that teaches 11th grade American history students about the 1st red scare, make it interactive. look up appropriate AP standards for what should be taught. make sure this is really good and students can use it easily”

It took it from there, doing research on AP standards, gathering information, and launching a website, as you can see. While I certainly wouldn’t trust Devin in its current state to produce accurate and hallucination-free results, you can see how the future might just be letting the AI do things, and sharing the results that work well.

Sharing what we learn

The lesson of innovation is that technology is only really useful when it is used. This might seem like a tautology, but it isn’t. When a new technology is introduced, people adapt it to solve the needs they have at hand, rather than simply following what the manufacturer of the technology intended. This leads to a lot of unexpected uses as the new technology is pushed to solve all sorts of novel problems. Right now, AI is in the hands of millions of educators, and they can use it to solve their own problems, in their own classrooms.

Once an exclusive privilege of million-dollar budgets and expert teams, education technology now rests in the hands of educators. While it's important to remain vigilant for potential hallucinations, errors, and biases, AI enables teachers to craft personalized prompts tailored to their local contexts, significantly bolstering their resources in the pursuit of quality education. But the only way to make sure that this revolution is positive and inclusive is to share what works.

Innovation requires cooperation. Nobody knows exactly where AI is useful, and where it is not, in advance. I have yet to see robust communities of educators (or many other professions) coming together to share what they create. Policymakers and institutional leaders can help make that happen. In the meantime, we hope that our prompts and blueprints can serve as the basis for ethical experimentation. Just make sure to share what you learn!

Hi Ethan,

Thanks for sharing this article!

I've been using GPT-4 quite a bit over the past year to help me develop learning materials.

Let me share a few examples.

I teach a bunch of different 1st and 2nd year comp sci courses and I have found that this tool saves me SO much time when creating learning materials for my courses. For example, in my introduction to Operating Systems course, I can feed GPT-4 a set of slides and ask it to come up with some relevant C coding for Linux exercises based on the material. It does this pretty darn well. Or I can provide a complex question and ask it to create 3 simpler questions that prepare students for the more complex question.

And for "Teaching the AI" I have given tutorials on how to use GPT-Builder tool that is available with GPT-4 to set up a custom GPT to assist learners in creating data visualization code. You can give the GPT pre-fab instructions, some conversation starters, and any extra knowledge you want it to have access to (ie. you can upload CSV files).

There are a bunch of these pre-fab GPTs out there for GPT-4. I have messed around with Khan Academy's "Khanmingo Lite" which is a code tutor and with a tool called GeoGPT+ which assists you in creating GIS maps from a dataset.

And finally, I second your comments on GPT-4's propensity for hallucinations. It is essential to research and back-check everything it produces as it is predictably unpredictable in its responses.

I love this post. I downloaded the paper and will apply what is in there for sure. I teach undergraduate and graduate business students, and I found it is more and more difficult to come up with something that will induce them to go deeper into their studies. AI is a help here, and a great one. My master one class is now hooked on the subject - leadership - because we solved problems with AI, and they enjoyed it, and I saw a lot of "AHA" moments in class. The book is great, it is not just a good read, but also I feel that I live the science-fiction I once dreamed of.