Against "Brain Damage"

AI can help, or hurt, our thinking

I increasingly find people asking me “does AI damage your brain?” It's a revealing question. Not because AI causes literal brain damage (it doesn't) but because the question itself shows how deeply we fear what AI might do to our ability to think. So, in this post, I want to discuss ways of using AI to help, rather than hurt, your mind. But why the obsession over AI damaging our brains?

Part of this is due to misinterpretation of a much-publicized paper out of the MIT Media Lab (with authors from other institutions as well), titled “Your Brain on ChatGPT.” The actual study is much less dramatic than the press coverage. It involved a small group of college students who were assigned to write essays alone, with Google, or with ChatGPT (and no other tools). The students who used ChatGPT were less engaged and remembered less about their essays than the group without AI. Four months later, nine of the ChatGPT users were asked to write the essay again without ChatGPT, and they performed worse than those who had not used AI initially (though were required to use AI in the new experiment) and showed less EEG activity when writing. There was, of course, no brain damage. Yet the more dramatic interpretation has captured our imagination because we have always feared that new technologies would ruin our ability to think: Plato thought writing would undermine our wisdom, and when cellphones came out, some people worried that not having to remember telephone numbers would make us dumber.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t worry about how AI impacts our thinking. After all, a key purpose of technology is to let us outsource work to machines. That includes intellectual work, like letting calculators do math or our cellphones record our phone numbers. And, when we outsource our thinking, we really do lose something — we can’t actually remember phone numbers as well, for example. Given that AI is such a general purpose intellectual technology, we can outsource a lot of our thinking to it. So how do we use AI to help, rather than hurt us?

The Learning Brain

The least surprising place where AI use can clearly hurt your mental growth is when you are trying to learn or synthesize new knowledge. If you outsource your thinking to the AI instead of doing the work yourself, then you will miss the opportunity to learn. We have evidence to back up this intuition, as my colleagues at Penn conducted an experiment at a high school in Turkey where some students were given access to GPT-4 to help with homework. When they were told to use ChatGPT without guidance or special prompting, they ended up taking a shortcut and getting answers. So even though students thought they learned a lot from ChatGPT's help, they actually learned less - scoring 17% worse on their final exam (compared to students who didn't use ChatGPT).

What makes this particularly insidious is that the harm happens even when students have good intentions. The AI is trained to be helpful and answer questions for you. Like the students, you may just want to get AI guidance on how to approach your homework, but it will often just give you the answer instead. As the MIT Media Lab study showed, this short-circuits the (sometimes unpleasant) mental effort that creates learning. The problem is not just cheating, though AI certainly makes that easier. The problem is that even honest attempts to use AI for help can backfire because the default mode of AI is to do the work for you, not with you.

Does that mean that AI always hurts learning? Not at all! While it is still early, we have increasing evidence that, when used with teacher guidance and good prompting based on sound pedagogical principles, AI can greatly improve learning outcomes. For example, a randomized, controlled World Bank study finds using a GPT-4 tutor with teacher guidance in a six week after school program in Nigeria had "more than twice the effect of some of the most effective interventions in education" at very low costs. While no study is perfect (in this case, the control was no intervention at all, so it is impossible to fully isolate the effects of AI, though they do try to do so), it joins a growing number of similar findings. A Harvard experiment in a large physics class found a well-prompted AI tutor outperformed active classes in learning outcomes; a study done in a massive programming class at Stanford found use of ChatGPT led to increased exam grades; a Malaysian study found AI used in conjunction with teacher guidance and solid pedagogy led to more learning; and even the experiment in Turkey that I mentioned earlier found that a better tutor prompt eliminated the drop in test scores from plain ChatGPT use.

Ultimately, it is how you use AI, rather than use of AI at all, that determines whether it helps or hurts your brain when learning. Moving away from asking the AI to help you with homework to helping you learn as a tutor is a useful step. Unfortunately, the default version of most AI models wants to give you the answer, rather than tutor you on a topic, so you might want to use a specialized prompt. While no one has developed the perfect tutor prompt, we have one that has been used in some education studies, and which may be useful to you and you can find more in the Wharton Generative AI Lab prompt library. Feel free to modify it (it is licensed under Creative Commons). If you are a parent, you can also act as the tutor yourself, prompting the AI “explain the answer to this question in a way I can teach my child, who is in X grade.” None of these approaches are perfect, and the challenges in education from AI are very real, but there is reason to hope that education will be able to adjust to AI in ways that help, and not hurt, our ability to think. That will involve instructor guidance, well-built prompts, and careful choices about when to use AI and when it should be avoided.

The Creative Brain

Just like in education, AI can help, or hurt, your creativity depending on how you use it. On many measures of creativity, AI beats most humans. To be clear, there is no one definition of creativity, but researchers have developed a number of flawed tests that are widely used to measure the ability of humans to come up with diverse and meaningful ideas. The fact that these tests were flawed wasn't that big a deal until, suddenly, AIs were able to pass all of them. The old GPT-4 beat 91% of humans on the a variation of the Alternative Uses Test for creativity and exceeds 99% of people on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. And we know these ideas are not just theoretically interesting. My colleagues at Wharton staged an idea generation contest: pitting ChatGPT-4 against the students in a popular innovation class that has historically led to many startups. Human judges rating the ideas showed that that ChatGPT-4 generated more, cheaper and better ideas than the students. The purchase intent from these outside judges was higher for the AI-generated ideas as well.

And yet, anyone who has used AI for idea generation will notice something these numbers don't capture. AI tends to act like a single creative person with predictable patterns. You'll see the same themes over and over like ideas involving VR, blockchain, the environment, and (of course) AI itself. This is a problem because in idea generation, you actually want a diverse set of ideas to pick from, not variations on a theme. Thus, there is a paradox: while AI is more creative than most individuals, it lacks the diversity that comes from multiple perspectives. Yet studies also show that people often generate better ideas when using AI than when working alone, and sometimes AI alone even outperforms humans working with AI. But, without caution, those ideas look very similar to each other when you see enough of them.

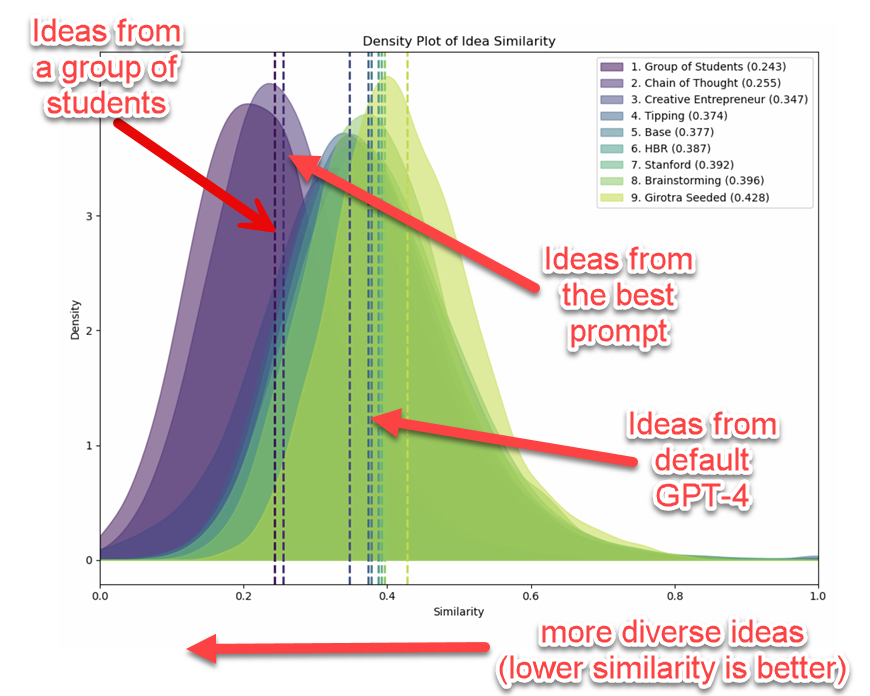

Part of this can be solved with better prompting. In a paper I worked on with Lennart Meincke and Christian Terwiesch, we found that better prompting can generate much more diverse ideas, if not quite as good as a group of students.

Here is the prompt, which was for GPT-4. It still works well for other AI models (though I suspect that reasoner models might actually be slightly less innovative than more traditional models):

Generate new product ideas with the following requirements: The product will target [market or customer]. It should be a [pick: physical good/service/software], not a [pick: physical good/service/software]. I'd like a product that could be sold at a retail price of less than about [insert amount].

The ideas are just ideas. The product need not yet exist, nor may it necessarily be clearly feasible. Follow these steps. Do each step, even if you think you do not need to. First generate a list of 100 ideas (short title only). Second, go through the list and determine whether the ideas are different and bold, modify the ideas as needed to make them bolder and more different. No two ideas should be the same. This is important! Next, give the ideas a name and combine it with a product description. The name and idea are separated by a colon and followed by a description. The idea should be expressed as a paragraph of 40-80 words. Do this step by step.But better prompting only solves part of the problem. The deeper risk is that AI can actually hurt your ability to think creatively by anchoring you to its suggestions. This happens in two ways.

First, there's the anchoring effect. Once you see AI's ideas, it becomes much harder to think outside those boundaries. It's like when someone tells you “don't think of a pink elephant.” AI's suggestions, even mediocre ones, can crowd out your own unique perspectives. Second, as the MIT study showed, people don’t feel as much ownership in AI generated ideas, meaning that you will disengage from the ideation process itself.

So how do you get AI's benefits without the brain drain? The key is sequencing. Always generate your own ideas before turning to AI. Write them down, no matter how rough. Just as group brainstorming works best when people think individually first, you need to capture your unique perspective before AI's suggestions can anchor you. Then use AI to push ideas further: “Combine ideas #3 and #7 in an extreme way,” “Even more extreme,” “Give me 10 more ideas like #42,” “User superheroes as inspiration to make the idea even more interesting.”

This principle becomes even more critical in writing. Many writers insist that "writing is thinking," and while this isn't universally true (I generated a pretty good Deep Research report on the topic if you want the details), it often is. The act of writing, and rewriting, and rewriting again helps you think through and hone your ideas. If you let AI handle your writing, you skip the thinking part entirely.

As someone for whom writing is thinking, I've needed to become disciplined. Every post I write, like this one, I do a full draft entirely without any AI use at all (beyond research help). This is often a long process, since I write and rewrite multiple times - thinking! Only when it is done do I turn to a number of AI models and give it the completed post and ask it to act as a reader: Was this unclear at any point, and how, specifically could I clarify the text for a non-technical reader? And sometime like an editor: I don’t like how this section ends, can you give me 20 versions of endings that might fit better. So go ahead, use AI to polish your prose and expand your possibilities. Just remember to do the thinking first, because that's the part that can't be outsourced.

The Collective Brain

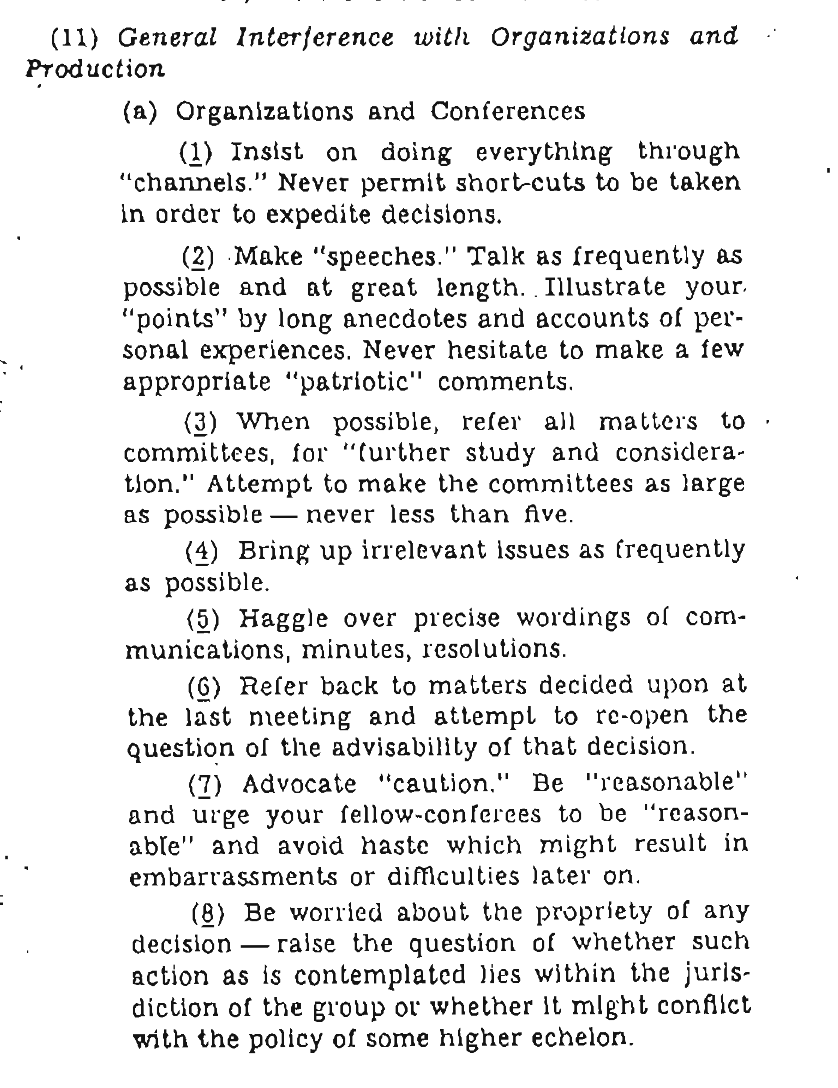

Another area where AI can hurt our thinking is through its impact on social processes. Ideally, the whole purpose of working on teams is that it can improve our performance - teams should be able to generate more ideas, be better able to see potential opportunities and pitfalls, and provide specialized skills and abilities to help execution. Meetings should be places where teams coordinate and solve problems. Of course, this is the ideal. In reality, one of the most revelatory management texts is actually this WWII guide to sabotage for civilians from the CIA's precursor. Look at the ideas for sabotaging office tasks to cause demoralization and delay and consider how many of them are normal parts of your meetings.

So it is no wonder that a significant early use of AI is to summarize meetings, and increasingly to summarize meetings you skip entirely. Of course, this raises existential questions like “why are we meeting in the first place if we can just read a summary?” or “should I just send an AI avatar of myself to meetings?” Obviously, there is no interaction, no teamwork, no meeting of the minds in a meeting where everyone is just there to read the transcript and nothing more. It just takes up time and effort, a form of organizational brain damage.

But rather than AI hurting our collective thinking, there is the option to have it help make us better. One interesting example is using AI as a facilitator. We created a prompt where AI acts as facilitator, creating customized tarot cards halfway through your meeting to help guide, rather than replace, your discussion. You give it a meeting transcript and it helps you bring out your best ideas (again, this is a Creative Commons license, so modify as needed, right now it works best on Claude, and okay on Gemini and o3)

This is just a fun example of the ways in which AI could be used to help our collective intelligence, but there is a need for many more experiments to figure out what works: using AI as a devil's advocate to surface unspoken concerns, having it identify whose voices aren't being heard in a discussion, or using it to find patterns in team dynamics that humans miss. The key is that AI enhances rather than replaces human interaction.

Against “Brain Damage”

AI doesn't damage our brains, but unthinking use can damage our thinking. What's at stake isn't our neurons but our habits of mind. There is plenty of work worth automating or replacing with AI (we rarely mourn the math we do with calculators), but also a lot of work where our thinking is important. For these problems, the research gives us a clear answer. If you want to keep the human part of your work: think first, write first, meet first.

Our fear of AI “damaging our brains” is actually a fear of our own laziness. The technology offers an easy out from the hard work of thinking, and we worry we'll take it. We should worry. But we should also remember that we have a choice.

Your brain is safe. Your thinking, however, is up to you.

Again, I love this! Exactly as I see it. AI does not kill your brain; you do it when you refuse to think. And there is no need to blame it on AI, just look at your smartphone. I was experimenting with AI in teaching, solely for my own purposes, to see what works better. Most of the students thought I was stupid or lazy when I let them use it, and I was curious whether they had learned anything at all. Not much, I have to admit. I did it poorly, but I learned from it. And I have no regrets; learning is a choice. There will always be people who skip it because they don't want to put in the effort. It is not the AI, as you say, it is us, being lazy humans.

I am a like a child who sees the candy she wants on the top shelf where she can't possibly reach, and along comes Ethan Mollick, a clever shelf stocker with a tall ladder. My eyes grow big, surely he will climb that ladder and get that candy for me. But no, he smiles and waves his hand as if to say, go ahead! I will make the climb for the prize, but not without trepidation!