You can't brute force the unsolvable

But a little finesse can help

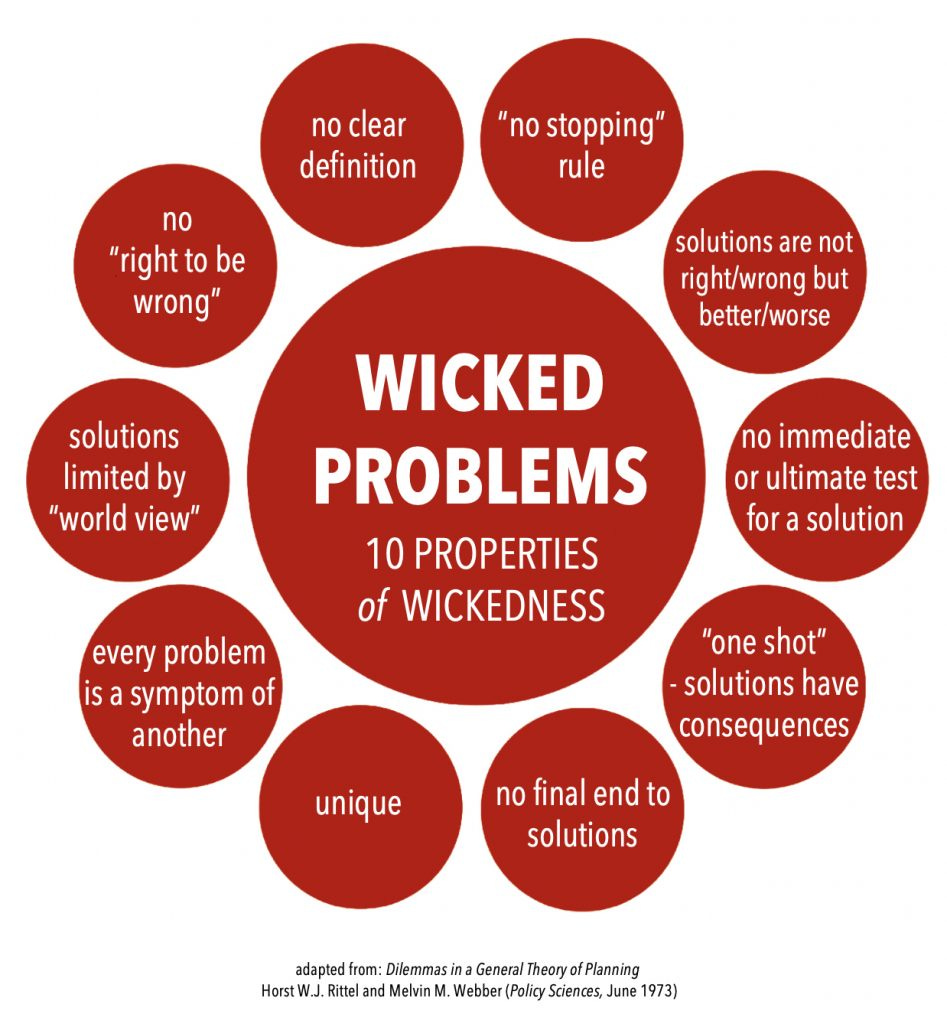

The world is awash in wicked problems. As laid out in an influential 1973 paper, wicked problems are those that are complex, uncertain and hard to evaluate. There is no general rule for addressing them, and acting on one part of them problem changes everything else. Thus, wicked problems cannot be simplified down to a single, easy answer.

But we can’t help ourselves. We love to simplify, to reduce problems to simple causes, to cut the Gordian Knot.

Entrepreneurs and engineers, especially, are trained to focus in on a solvable problem, and start from there. As a really fascinating recent paper by Gras, Conger, and Jenkins has pointed out, this “reductive tendency” can create more issues than it solves.

The act of simplifying down a problem creates a caricature of the real issue and solving the caricature doesn’t solve the problem - it can make it worse. Even very good-natured efforts can lead to problems when they ignore complex social realities. For example, the noble One Laptop per Child program, launched out of the MIT Media Lab in 2005, aimed to distribute ultra-cheap laptops to the poorest children in the world. It was, in large part, based on the constructivist dream that kids, given the right technological tools, could teach themselves vital skills that would help bootstrap them out of poverty. Because it was so simple (literally airdrop laptops into Africa!) it was a seductive idea for both the engineers and educators creating the program, and the governments interested in funding it.

But the program never achieved its goals. Much of the failure of the program was blamed on technology, but, even if the laptops worked, the problem was obviously more complex. Would $100 laptops be better than the same money spent on teachers? How would they fit into a variety of culutral traditions and socioeconomic contexts? How many students would be left behind if the laptop’s teaching software didn’t work for them or the laptop broke? Educating the developing world is a wicked problem that cannot be solved with technology alone, shorn of all other contexts. The complexity of people and society gets in the way. The same story applies to many other wicked problems, from climate change to vaccination programs.

"If only it weren't for the people, the goddamned people," said Finnerty, "always getting tangled up in the machinery. If it weren't for them, earth would be an engineer's paradise." - Kurt Vonnegut, Player Piano

But most of the most important problems in the world are wicked problems. So where does that leave us? Almost every paper on wicked problems seems to trail off a bit here. Often, they discuss the need to embrace complexity, or be interdisciplinary, or to spend a lot of time learning about the issue. I find all of these answers unsatisfying because they don’t actually suggest how to take action. Caution can easily turn into passivity, and many wicked problems need to be addressed, because the risk of not doing so is greater than the risk of failure.

I think, instead, the solution to wicked problems may be to challenge a core claim of “wickedness:” that wicked problems cannot be solved by trial and error because every attempted solution shifts the nature of the problem. This may have always been true in 1973 but things have changed in the past 50 years. I think this principle is often wrong today for two reasons: (1) we have developed much better tools for rapidly developing and testing solutions and (2) it gives us too much credit for our ability to change the world.

On the first point, a number of methdological and process improvements - agile software development, simple ways to do fast A/B testing, more sensitive tools to measure outcomes - have made it easier for us to conduct rapid, low risk experimentation than it used to be. It is not always necessary to try to solve the problem in one shot, as the original definition for wicked problems implied. For example, a modern approach to One Laptop per Child would be to first consider measurable outcomes for the program, and then to design some cheap experiments to test the underlying assumptions about those outcomes. Rather than focusing on cost first, limited tests using conventional laptops with the early versions of the software might have provided valuable insights into the possible wicked dimensions of the problem before major resources were commited to the program.

Second, a key lesson of the recent reproducibility crisis in science has been that most interventions don’t do much. Most slippery slopes aren’t actually that slippery, and most small-scale actions we take do not have world-altering consequences. Change is hard. All of this means that experimentation is less risky than the original formulation of wicked problems tends to imply.

So what does this mean for wicked problems? Baseless reduction doesn’t help solve wicked problems, but a healthy understanding of their complexity might serve as a basis for a solution. And, once that understanding is established, judicious, well-designed experiments might help gently unpick the Gordian Knots of the hardest problems we face today. Having a respect for wicked problems is important, but we don’t need to be paralyzed by their complexity.

I think, by all means, the original definition of wicked problems is outdated and outright problematic. It actually surprises me that by then the idea of small experimental interventions was so unimaginable.

Lovely articulation of the idea, Ethan, and the schematic helps distil the key points. I'm wondering how you think we could run A/B tests or randomised controlled trials on populations to test proposed policies (where policy planning is a wicked problem, for example). Where would you fence the idea of using rapid experimentation to solve wicked problems?

From a systems pov, problems occur when the goals of subsystems are at odds with each other. Romania banned abortion to up the birth rate, but child and maternal mortality shot up because of unsafe and illegal abortions, orphanages swelled in size, official birth rate stayed out.