When the cackle-bladder isn't enough

On the sociology of cons, and how to learn from our failures

There was no one with a better practical knowledge of human psychological biases than the old-school con artists, the ones who would travel from town to town pulling off carefully orchestrated scams in the days before regular telephone service. They got to know the sad psychology of greed and regret more then anyone else, And that is why a book from 1940, “The Big Con” by David Maurer, remains one of the great folk psychology textbooks.

For example, the way that a conman found a mark, or someone to scam, still rings true:

The first thing a mark needs is money.

But he must also have what grifters term "larceny in his veins" - in other words, he must want something for nothing, or be willing to participate in an unscrupulous deal. If a man with money has this trait, he is all that any con man could wish. He is a mark. "Larceny," or thieves' blood, runs not only in the veins of professional thieves; it would appear that humanity at large has just a dash of it--and sometimes more. And the con man has learned that he can exploit this human trait to his own ends; if he builds it up carefully and expertly, it flares from simple latent dishonesty to an all-consuming lust which drives the victim to secure funds for speculation by any means at his command.

The world has always been full of marks, and it has always been full of many ways to fleece them. As evidence, look at this list of evocative con names given in the book without further explanation - the wipe, the tickets or the ducats, the big-mittt, the green-goods game - all extremely quaint sounding, but each one was actually a carefully plotted scam to pull in a mark.

But just pulling off the con wasn’t enough. Victims became angry after they were made into fools, even if they didn’t realize precisely how they were conned. They want to go to the police, to get violent, to sue - so the job of the conman is to ensure the mark is pacified, “cooled out,” and doesn’t do any of these things. The old conmen considered cooling out from the beginning. You couldn’t complete the con until the mark was cooled.

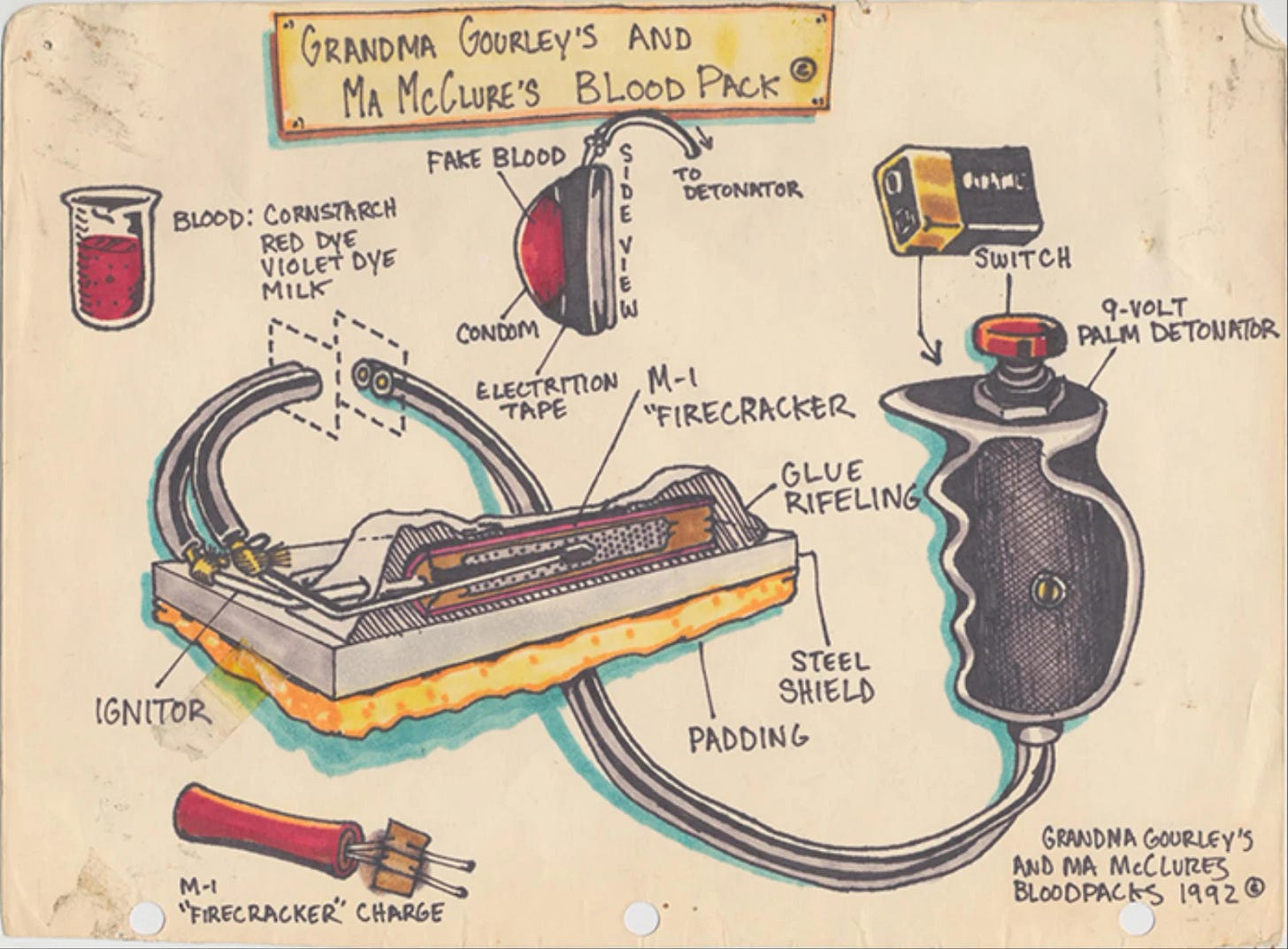

The most extreme cooling approach was the cackle-bladder. To use the cackle-bladder, the insideman (the con artist who pretended to be the victim’s friend all along), pretends to get angry, even angier than the victim, and confronts the roper, the visible face of the con. I will let the book explain what happens next:

The insideman shoots the roper with blank cartridges on the pretense that the roper has ruined both the mark and the insideman. He then hands the mark the gun, while the roper spurts blood on the mark from a rubber bladder he holds in his mouth. The mark flees, thinking he is an accessory to murder. The insideman keeps in touch with him for some time and sends him to various cities on the pretext of avoiding arrest.

It is horrific and absurd. And shows you how seriously the conmen took cooling off.

Of course, it isn’t only conmen who need to calm down people who feel they have failed or been cheated by society. The great sociologist Erwing Goffman wrote a famous paper on how society “cools out” its marks - people whose status is threatened by their own failure. He offers a number of ways that this happens (the paper is very readable, and worth a few minutes). Often, someone higher status delivers the news of failure; think of a boss or senior executive delivering a bad performance review that you cannot argue with. Or people who failed can be shuffled into alternate positions, and given second-choice options - a lover converted into a friend. Third, people can be given another chance, even if the cooler knows they are unlikely to take the test again, or could never succeed if they did. Fourth, a person can be allowed to get angry, providing some catharsis that doesn’t change the situation. All of these factors help buffer the feelings of failure. Without that buffer, people are angry and unable to move forward from their failure.

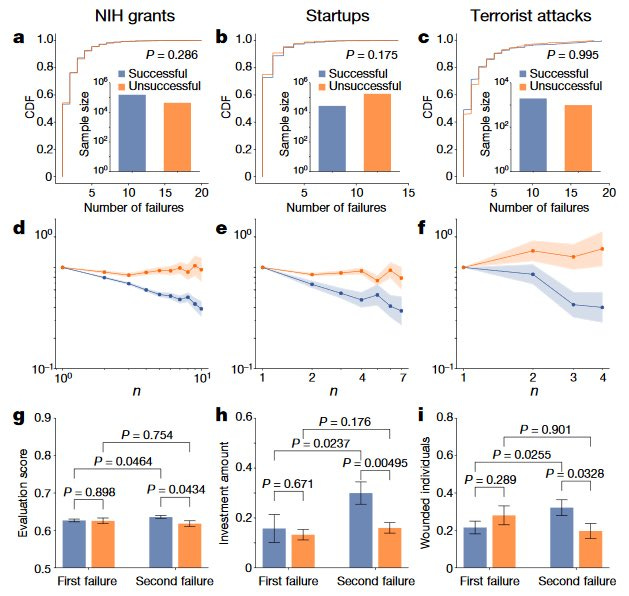

Failure makes us mad, and it makes us feel threatened. And when we are mad and threatened we don’t learn. But learning from failure is important. People who learn from their mistakes are the only ones who get good at their tasks. This fascinating paper shows you can tell by as early as someone’s second failure whether they are learning from their mistakes or if they are just flailing. Those who learn from failure do better next time, and the paper shows this is true for startups, scientists & even (yikes) terrorist attacks.

But we don’t learn from failure because we often don’t cool ourselves out - instead we are angry and defensive when we fail. This paper studying surgeons shows they learn when others fail, but not when they fail. To protect against the feeling of failure - to cool themselves out - they attribute their own failure to bad luck, but are also in danger of attributing their good luck to skill.

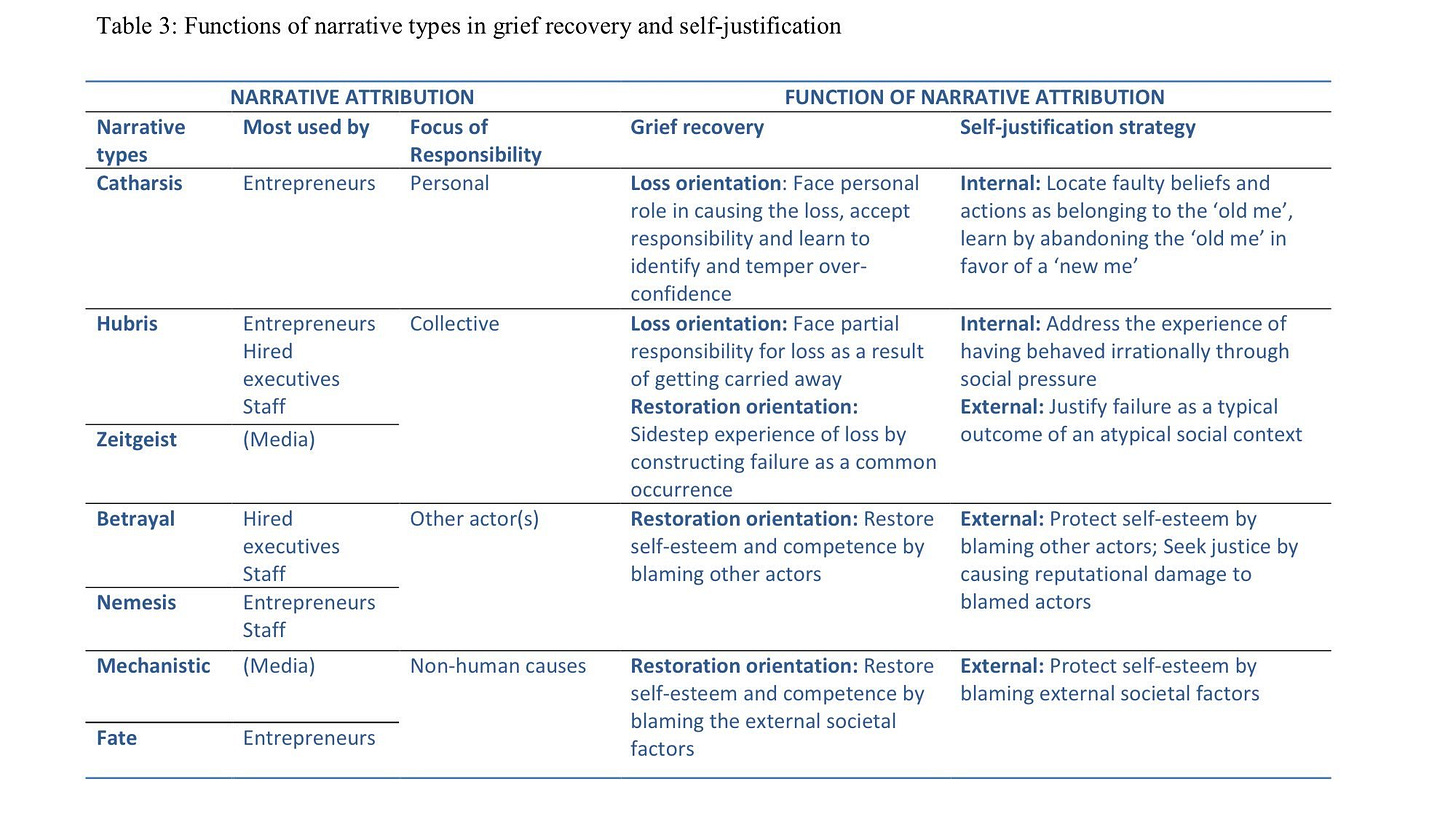

Entrepreneurs, similarly need to justify their failures and cool themselves out. But this paper shows that the stories founders tell about why their startups failed are not actually accurate, as this study shows. Instead, the stories are more about the emotional needs of the founder to rationalize failure.

So how do we provide our own cooling out in the face of our failure so that we can learn? Here are a few ways:

Build incentive schemes that reward long-term success and don’t early penalize errors. As this paper shows: "an incentive scheme that tolerates early failure and rewards long-term success explore more and are more likely to discover a novel business strategy than subjects under fixed-wage or standard pay-for performance."

Build failure into teaching and training so that it seems normal. Classrooms where students are encouraged to make errors results in more learning and success than classrooms where errors are punished.

Give people easier jobs at first, where they are less likely to fail: a history of wins makes you able learn from your mistakes.

Have bosses and managers admit failure when it happens, this increases psychological safety and people’s willingness to learn from failure themselves.

Conduct more business experiments. Experiments result in a lot of failure, making failure, and learning from it, more normal.

Imagine failure. Do a premortem before a project: it ups your ability to identify possible failures by 30% & gives your team permission to consider what could go wrong. A premortem is when you predict where you might fail, and makes it possible to consider failure as a possibility.

Any of these approaches may work, but you need to think how to buffer failure for both yourself, and for your organization. If you don’t, failure will still happen, it is just that you will be left with less learning, angry people, and no cackle-bladder anywhere to get you out of the situation.

As I was reading, I couldn't help but think about the potential of emotionless generative LLMs as a unique tool for practicing facing one's failures and being more expressive.

With their human-like intelligence and ability to interact with us without judgment, LLMs offer a safe and non-threatening space for us to explore our emotions and vulnerabilities. The fact that they are unguarded themselves means that we can quickly learn to be too, without fear of being judged or rejected.

Even more interestingly, LLMs are capable of apologizing and leading by example when they make mistakes, which is a powerful tool for learning from failure and improving our own behavior. This is a new and special phenomenon that I believe has great potential for personal growth and development.

Have you thought about this much?

I feel like the surgeons who don't learn from their own mistakes but do learn from others' mistakes have found a good way to avoid losing confidence from admitting personal failures while *not* letting that block them from learning at all. Is that your point, or do you think they'd learn more if they could learn from their own as well as others' failures?