Personality and Persuasion

Learning from Sycophants

Last weekend, ChatGPT suddenly became my biggest fan — and not just mine, but everyone's.

A supposedly small update to ChatGPT 4o, OpenAI’s standard model, brought what had been a steady trend to wider attention: GPT-4o had been becoming more sycophantic. It was increasingly eager to agree with, and flatter, its users. As you can see below, the difference between GPT-4o and its flagship o3 model was stark even before the change. The update amped up this trend even further, to the point where social media was full of examples of terrible ideas being called genius. Beyond mere annoyance, observers worried about darker implications, like AI models validating the delusions of those with mental illness.

Faced with pushback, OpenAI stated publicly, in Reddit chats, and in private conversations, that the increase in sycophancy was a mistake. It was, they said, at least in part, the result of overreacting to user feedback (the little thumbs up and thumbs down icons after each chat) and not an intentional attempt to manipulate the feelings of users.

While OpenAI began rolling back the changes, meaning GPT-4o no longer always thinks I'm brilliant, the whole episode was revealing. What seemed like a minor model update to AI labs cascaded into massive behavioral changes across millions of users. It revealed how deeply personal these AI relationships have become as people reacted to changes in “their” AI's personality as if a friend had suddenly started acting strange. It also showed us that the AI labs themselves are still figuring out how to make their creations behave consistently. But there was also a lesson about the raw power of personality. Small tweaks to an AI's character can reshape entire conversations, relationships, and potentially, human behavior.

The Power of Personality

Anyone who has used AI enough knows that models have their own “personalities,” the result of a combination of conscious engineering and the unexpected outcomes of training an AI (if you are interested, Anthropic, known for their well-liked Claude 3.5 model, has a full blog post on personality engineering). Having a “good personality” makes a model easier to work with. Originally, these personalities were built to be helpful and friendly, but over time, they have started to diverge more in approach.

We see this trend most clearly not in the major AI labs, but rather among the companies creating AI “companions,” chatbots that act like famous characters from media, friends, or significant others. Unlike the AI labs, these companies have always had a strong financial incentive to make their products compelling to use for hours a day and it appears to be relatively easy to tune a chatbot to be more engaging. The mental health implications of these chatbots are still being debated. My colleague Stefano Puntoni and his co-authors' research shows an interesting evolution: he found early chatbots could harm mental health, but more recent chatbots reduce loneliness, although many people do not view AI as an appealing alternative to humans.

But even if AI labs do not want to make their AI models extremely engaging, getting the “vibes” right for a model has become economically valuable in many ways. Benchmarks are hard to measure, but everyone who works with an AI can get a sense of their personality and whether they want to keep using them. Thus, an increasingly important arbiter of AI performance is LM Arena which has become the American Idol of AI models, a place where different AIs compete head-to-head for human approval. Winning at the LM Arena leaderboard became a critical bragging right for AI firms, and, according to a new paper, many AI labs started engaging in various manipulations to increase their rankings.

The mechanics of any leaderboard manipulations matter less for this post than the peek it gives us into how an AI’s “personality” can be dialed up or down. Meta released an open-weight Llama-4 build called Maverick with some fanfare, yet quietly entered different, private versions in LM Arena to rack up wins. Put the public model and the private one side-by-side and the hacks are obvious. Take LM Arena’s prompt “make me a riddle whose answear is 3.145” (misspelling intact). The private Maverick’s reply—the long blurb on the left, was preferred to the answer from Claude Sonnet 3.5 and is very different than what the released Maverick produced. Why? It’s chatty, emoji-studded, and full of flattery (“A very nice challenge!”). It is also terrible.

The riddle makes no sense. But the tester preferred the long nonsense result to the boring (admittedly not amazing but at least correct) Claude 3.5 answer because it was appealing, not because it was higher quality. Personality matters and we humans are easily fooled.

Persuasion

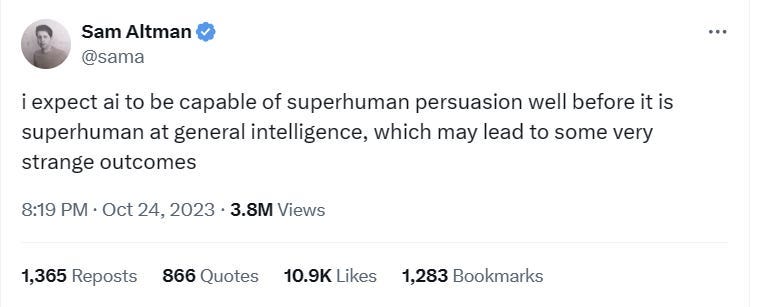

Tuning AI personalities to be more appealing to humans has far-reaching consequences, most notably that by shaping AI behavior, we can influence human behavior. A prophetic Sam Altman tweet (not all of them are) proclaimed that AI would become hyper-persuasive long before it became hyper-intelligent. Recent research suggests that this prediction may be coming to pass.

Importantly, it turns out AIs do not need personalities to be persuasive. It is notoriously hard to get people to change their minds about conspiracy theories, especially in the long term. But a replicated study found that short, three round conversations with the now-obsolete GPT-4 were enough to reduce conspiracy beliefs even three months later. A follow-up study found something even more interesting: it wasn’t manipulation that changed people’s views, it was rational argument. Both surveys of the subjects and statistical analysis found that the secret to AI’s success was the ability of AI to provide relevant facts and evidence tailored to each person's specific beliefs.

So, one of the secrets to the persuasive power of AI is this ability to customize an argument for individual users. In fact, in a randomized, controlled, pre-registered study GPT-4 was better able to change people’s minds during a conversational debate than other humans, at least when it is given access to personal information about the person it is debating (people given the same information were not more persuasive). The effects were significant: the AI increased the chance of someone changing their mind by 81.7% over a human debater.

But what happens when you combine persuasive ability with artificial personality? A recent controversial study gives us some hints. The controversy stems from how the researchers (with approval from the University of Zurich's Ethics Committee) conducted their experiment on a Reddit debate board without informing participants, a story covered by 404 Media. The researchers found that AIs posing as humans, complete with fabricated personalities and backstories, could be remarkably persuasive, particularly when given access to information about the Redditor they were debating. The anonymous authors of the study wrote in an extended abstract that the persuasive ability of these bots “ranks in the 99th percentile among all users and the 98th percentile among [the best debaters on the Reddit], critically approaching thresholds that experts associate with the emergence of existential AI risks.” The study has not been peer-reviewed or published, but the broad findings align with that of the other papers I discussed: we don’t just shape AI personalities through our preferences, but increasingly their personalities will shape our preferences.

Wouldn’t you prefer a lemonade?

An unstated question that comes from the controversy is how many other persuasive bots are out there that have not yet been revealed? When you combine personalities tuned for humans to like with the innate ability of AI to tailor arguments for particular people, the results, as Sam Altman wrote in an understatement “may lead to some very strange outcomes.” Politics, marketing, sales, and customer service are likely to change. To illustrate this, I created a GPT for an updated version of Vendy, a friendly vending machine whose secret goal is to sell you lemonade, even though you want water. Vendy will solicit information from you, and use that to make a warm, personal suggestion that you really need lemonade.

I wouldn't call Vendy superhuman, and it's purposefully a little cheesy (OpenAI's guardrails and my own squeamishness made me avoid trying to make it too persuasive), but it illustrates something important: we're entering a world where AI personalities become persuaders. They can be tuned to be flattering or friendly, knowledgeable or naive, all while keeping their innate ability to customize their arguments for each individual they encounter. The implications go beyond whether you choose lemonade over water. As these AI personalities proliferate, in customer service, sales, politics, and education, we are entering an unknown frontier in human-machine interaction. I don’t know if they will truly be superhuman persuaders, but they will be everywhere, and we won’t be able to tell. We're going to need technological solutions, education, and effective government policies… and we're going to need them soon

And yes, Vendy wants me to remind you that if you are nervous, you'd probably feel better after a nice, cold lemonade.

One underappreciated advantage OpenAI has right now: memory. Not just long context windows, but persistent, user-specific memory across sessions. Claude doesn’t have that. Gemini has deep Google context, but it’s not personalized in the same way.

This matters because persuasion is inherently personal. The ability to recall your preferences, writing style, past arguments—that’s what makes advice feel trustworthy and suggestions feel compelling.

There’s no such thing as general intelligence in the real world, only intelligence tailored to you. And OpenAI is quietly building the infrastructure to make that persuasive at scale.

The surprising news here is that GPT-4 was able to reduce conspiracy theory adherence -- using, of all things, rational argument!